I'm certainly not quitting this blog or something--in fact what I'm saying now won't change anything in practice--but I do find myself having a lot less to say. It's frustrating because I feel like when I don't update regularly, people stop reading, but I don't want to just write a lot of posts that I haven't thought through. I also feel uncomfortable about writing a lot of posts with very personal information, partly because I guess I feel like it's unwise when I use my real name on this blog, but also because I always prided myself on writing a blog that was more based in ideas than in my personal experience (even though my experience has always been an element).

When I started this blog, which was about a year and a half ago, I was overflowing with things to say about disability that I had not been able to express, and had not heard other people say either. I would wake up in the morning and know what I was going to write about, and several times a day I would experience the feeling again. For probably eight months it was like this, but it hasn't been like that for a while.

I still definitely learn and have experiences and realize things and get ideas, but there isn't anything built up anymore really--new stuff comes in at its ordinary and fairly slow rate. Don't leave please.

Amanda

31 December, 2010

26 December, 2010

probably going to delete this because it makes me sound super unstable, so enjoy it while you can.

I'm going to a doctor tomorrow to hopefully get a lot of cognitive/learning testing, because even though I've been diagnosed with ASD a few times and stuff, a word like ASD isn't really useful when you are just really stupid at the things I'm stupid at. And I really want to know, and be able to tell people, exactly what's going on. My mom told me to write some stuff to talk to him about and I wrote this (but I won't say all of this obviously, but I thought you might think it was interesting):

Emotional Problems--which I understand are going to seem like the main thing, and it’s going to seem like, why am I going to a learning specialist for this stuff, but bear with me.

Anxiety, which sometimes feels like stereotypical anxiety but usually feels like a boring or distracting thing, like fatigue, or dissociation/derealization (I think this is interesting: I have a very strong sense of time and past, so sometimes people and things from a very specific time period will become unreal, while I, and people and things from other periods of my life, will still feel real), or a really strong desire for something to happen, or a desire to leave, when I’m waiting in a line or in class--like, a sudden sense of intense anger if for example someone cuts in front of me in line or my professor says, “well, let’s just stay a minute longer so we can all finish translating this”

Suicidal ideation, et. al. Mostly, I had a really strong interest in getting a traumatic brain injury by getting myself hit by a car, or jumping out a window headfirst. About the time I turned 22, it was all I could think about, since if you get a TBI before age 22, you’re classified legally as “developmentally disabled,” but if you get it after age 22, you’re classified as “elderly/physically disabled,” and you get worse services. Besides, I already have a DD since I have autism, and I’d rather get services with people like me. So I spent the days before I turned 22 thinking about how I should really probably get hit by a car. And then a few weeks later, after I’d missed the deadline to get my TBI, I started thinking maybe I should just actually kill myself. I know all this seems unreasonable, but I’m getting to the point. Just from knowing a bunch of other people with autism, I know that it’s not all that weird for me to have the kind of cognitive problems I have, but a lot of people don’t know that, even professionals. There’s no easy way to explain to people why stuff is so hard for me. I feel terrible. I feel stupid and lazy. I hate asking for extensions from professors, or help from disability services at school, and it’s really hard because I have to explain everything, and I usually feel like they resent me. I really hate the disability services person at my college, because in my brief dealings with her she’s made it really obvious that she doesn’t think I have any real problems--but I had to transfer my credits from study abroad, and I really needed help figuring out what to do, and if I didn’t do it I wouldn’t be able to graduate--so I arranged to meet with her. All I needed was for someone to sit with me while I made a list of everything I needed to do to complete the process; and she did that, but she was still really patronizing. (I’m actually not as paranoid as I sound; I know several people who have had bad experiences with her.)

Last summer, I worked at a sleepaway camp for disabled adults. I mostly really like working with other people with DDs, because it’s a more comfortable environment and I don’t have to worry whether anyone is noticing that I’m disabled, because I’m not the only disabled person there. I mostly enjoyed my job. But at one point, I had these campers who were older men with Down Syndrome and they would all get really confused when they were getting dressed and brushing their teeth and showering, and basically needed help staying on track for everything. Which is basically what I’m like, unless I try really hard and focus really hard. I wasn’t really able to shower easily, without getting off track, until I was probably 19 or 20.

So, it was really hard for me to remember everything I had to remember to help these guys get dressed, and stuff. I felt so incredibly incompetent and I felt like none of the other staff understood why it was so hard for me. I mean, most of them didn’t know I have autism, but even the people who I was more friendly with and had told--I mean, people just think autism means you’re socially awkward or something. So I was just getting so worn out, and I just couldn’t help feeling super jealous, and wishing I was more severely disabled like they were, so that it would be someone else’s responsibility to make me get dressed in the morning and take showers and stuff. And that if I couldn’t do something, people would just think that was understandable, and help me, instead of thinking I was an asshole, and I wouldn’t feel like I had to just hide it or lie about it because that’s the polite thing to do. So this is why I want a brain injury, or sometimes want to kill myself. Not exactly because of the cognitive problems, but because they’re not something I can prove, and I feel like a stupid person who’s probably just lying and being really lazy. I sort of hope that you’ll give me these tests and they’ll come back saying that I have the working memory of an 5-year-old, or something--like, I don’t even need to tell other people that, if I just knew that for sure, I’d be so happy.

But anyway.

Cognitive Problems--

shit for brains

i.e.:

it’s really hard to remember anything short-term. You can’t tell right now because I’m not in school, but usually I have a bunch of instructions written on my hand and on my computer keyboard so I can remember to do things. I try to keep assignment books or whatever, but it takes a lot of mental switching around to write down all the assignments, and it takes a lot to remember to look at the assignment book, so it doesn’t really work. So I put it on my computer and my hand because I don’t have to remember to look at them. As soon as I stop looking at something, it tends to disappear from my consciousness unless I try really hard to keep it there.

Also it’s hard to transition. Ever. It’s just really unpleasant to have to switch from doing one thing to doing something else, or to have my day go differently from the way I expected. For example, once I was really upset because a professor and the other people in a class told me that I would have to switch my work shifts to a different day, because the professor wanted to move the class to a different time. I didn’t know how to switch my shift because I don’t do things like that.

I just need someone to walk me through things, like, figuring out how to do stuff, but it’s almost impossible to ask someone to do that and that is why I sometimes want to kill myself--it’s not the fact that stuff is hard, it’s the fact that such stupid things are hard and it is so close to being easy. If it was just someone’s job to help me do stuff for an hour a week, my life would be completely different, but it’s not, so it’s not.

That is all I can remember right now, and it doesn’t really seem like a big deal--it even seems funny. And it is on the small scale. But if you’re actually in college and you can’t remember things and it’s hard to transition, and then you get to feeling anxious about all the things you’re trying to keep in your head, when the absolute most pleasant thing would be to forget them because you probably won’t be able to do them anyway, so you start cutting corners and dropping little things, because you don’t want to get upset; and you can’t stand to think about how things really are in terms of school, because you’re afraid you would get so upset you’d never come back from it; and you can’t really ask people for help because no one really gets or is trained for this stuff, and you don’t exactly understand yourself what is wrong...well, then, you just start thinking it would be better to die, not because you’re sad all the time or something, but just because it is the only easy answer to the question.

Emotional Problems--which I understand are going to seem like the main thing, and it’s going to seem like, why am I going to a learning specialist for this stuff, but bear with me.

Anxiety, which sometimes feels like stereotypical anxiety but usually feels like a boring or distracting thing, like fatigue, or dissociation/derealization (I think this is interesting: I have a very strong sense of time and past, so sometimes people and things from a very specific time period will become unreal, while I, and people and things from other periods of my life, will still feel real), or a really strong desire for something to happen, or a desire to leave, when I’m waiting in a line or in class--like, a sudden sense of intense anger if for example someone cuts in front of me in line or my professor says, “well, let’s just stay a minute longer so we can all finish translating this”

Suicidal ideation, et. al. Mostly, I had a really strong interest in getting a traumatic brain injury by getting myself hit by a car, or jumping out a window headfirst. About the time I turned 22, it was all I could think about, since if you get a TBI before age 22, you’re classified legally as “developmentally disabled,” but if you get it after age 22, you’re classified as “elderly/physically disabled,” and you get worse services. Besides, I already have a DD since I have autism, and I’d rather get services with people like me. So I spent the days before I turned 22 thinking about how I should really probably get hit by a car. And then a few weeks later, after I’d missed the deadline to get my TBI, I started thinking maybe I should just actually kill myself. I know all this seems unreasonable, but I’m getting to the point. Just from knowing a bunch of other people with autism, I know that it’s not all that weird for me to have the kind of cognitive problems I have, but a lot of people don’t know that, even professionals. There’s no easy way to explain to people why stuff is so hard for me. I feel terrible. I feel stupid and lazy. I hate asking for extensions from professors, or help from disability services at school, and it’s really hard because I have to explain everything, and I usually feel like they resent me. I really hate the disability services person at my college, because in my brief dealings with her she’s made it really obvious that she doesn’t think I have any real problems--but I had to transfer my credits from study abroad, and I really needed help figuring out what to do, and if I didn’t do it I wouldn’t be able to graduate--so I arranged to meet with her. All I needed was for someone to sit with me while I made a list of everything I needed to do to complete the process; and she did that, but she was still really patronizing. (I’m actually not as paranoid as I sound; I know several people who have had bad experiences with her.)

Last summer, I worked at a sleepaway camp for disabled adults. I mostly really like working with other people with DDs, because it’s a more comfortable environment and I don’t have to worry whether anyone is noticing that I’m disabled, because I’m not the only disabled person there. I mostly enjoyed my job. But at one point, I had these campers who were older men with Down Syndrome and they would all get really confused when they were getting dressed and brushing their teeth and showering, and basically needed help staying on track for everything. Which is basically what I’m like, unless I try really hard and focus really hard. I wasn’t really able to shower easily, without getting off track, until I was probably 19 or 20.

So, it was really hard for me to remember everything I had to remember to help these guys get dressed, and stuff. I felt so incredibly incompetent and I felt like none of the other staff understood why it was so hard for me. I mean, most of them didn’t know I have autism, but even the people who I was more friendly with and had told--I mean, people just think autism means you’re socially awkward or something. So I was just getting so worn out, and I just couldn’t help feeling super jealous, and wishing I was more severely disabled like they were, so that it would be someone else’s responsibility to make me get dressed in the morning and take showers and stuff. And that if I couldn’t do something, people would just think that was understandable, and help me, instead of thinking I was an asshole, and I wouldn’t feel like I had to just hide it or lie about it because that’s the polite thing to do. So this is why I want a brain injury, or sometimes want to kill myself. Not exactly because of the cognitive problems, but because they’re not something I can prove, and I feel like a stupid person who’s probably just lying and being really lazy. I sort of hope that you’ll give me these tests and they’ll come back saying that I have the working memory of an 5-year-old, or something--like, I don’t even need to tell other people that, if I just knew that for sure, I’d be so happy.

But anyway.

Cognitive Problems--

shit for brains

i.e.:

it’s really hard to remember anything short-term. You can’t tell right now because I’m not in school, but usually I have a bunch of instructions written on my hand and on my computer keyboard so I can remember to do things. I try to keep assignment books or whatever, but it takes a lot of mental switching around to write down all the assignments, and it takes a lot to remember to look at the assignment book, so it doesn’t really work. So I put it on my computer and my hand because I don’t have to remember to look at them. As soon as I stop looking at something, it tends to disappear from my consciousness unless I try really hard to keep it there.

Also it’s hard to transition. Ever. It’s just really unpleasant to have to switch from doing one thing to doing something else, or to have my day go differently from the way I expected. For example, once I was really upset because a professor and the other people in a class told me that I would have to switch my work shifts to a different day, because the professor wanted to move the class to a different time. I didn’t know how to switch my shift because I don’t do things like that.

I just need someone to walk me through things, like, figuring out how to do stuff, but it’s almost impossible to ask someone to do that and that is why I sometimes want to kill myself--it’s not the fact that stuff is hard, it’s the fact that such stupid things are hard and it is so close to being easy. If it was just someone’s job to help me do stuff for an hour a week, my life would be completely different, but it’s not, so it’s not.

That is all I can remember right now, and it doesn’t really seem like a big deal--it even seems funny. And it is on the small scale. But if you’re actually in college and you can’t remember things and it’s hard to transition, and then you get to feeling anxious about all the things you’re trying to keep in your head, when the absolute most pleasant thing would be to forget them because you probably won’t be able to do them anyway, so you start cutting corners and dropping little things, because you don’t want to get upset; and you can’t stand to think about how things really are in terms of school, because you’re afraid you would get so upset you’d never come back from it; and you can’t really ask people for help because no one really gets or is trained for this stuff, and you don’t exactly understand yourself what is wrong...well, then, you just start thinking it would be better to die, not because you’re sad all the time or something, but just because it is the only easy answer to the question.

25 December, 2010

Jess gave me a Stylish Blogger Award, but I'm not. She always has nice shoes and is standing properly in her facebook pictures. I look like this (fact one, except I usually don't wear glasses and my hair is more vividly colored):

My clothes are always gross and besides, I write on them.

Anyway, I am supposed to say 7 lesser-known things about myself and tag three other people. I like Julia and the untoward lady and I like Fiona who draws PICTURES! Maybe she could draw 7 pictures about herself.

2. I hate Christmas

3. I smoke a lot but not when I'm with my parents (which I have been since Wednesday--I just got through withdrawal and life is SWELL)

4. I drink a lot of Diet Coke, and just saying I drink a lot of it is kind of understating the situation because I've seriously almost lost friends because of the way I am about Diet Coke

5. I'm left-handed

6. I like boys too much (maybe any amount is too much when you're gay as shit)

7. I'm a neoplatonic Christian sort of, but you knew that already

My clothes are always gross and besides, I write on them.

Anyway, I am supposed to say 7 lesser-known things about myself and tag three other people. I like Julia and the untoward lady and I like Fiona who draws PICTURES! Maybe she could draw 7 pictures about herself.

2. I hate Christmas

3. I smoke a lot but not when I'm with my parents (which I have been since Wednesday--I just got through withdrawal and life is SWELL)

4. I drink a lot of Diet Coke, and just saying I drink a lot of it is kind of understating the situation because I've seriously almost lost friends because of the way I am about Diet Coke

5. I'm left-handed

6. I like boys too much (maybe any amount is too much when you're gay as shit)

7. I'm a neoplatonic Christian sort of, but you knew that already

people you want to hide vs. people who actually don't exist

Several years ago I remember reading a New Yorker piece by one of the Autism Pop Culture kids--John Elder Robison maybe? Whoever he was, he said something about having had to create his personality from scratch, instead of naturally having one. And I was like, "yeah totally this is such a good description of what ASD is like! I can relate to this better than anything else I've ever read!"

Whereas now I'm kind of like...seriously?

It's weird to say this because a few years ago I don't think there was anything I hated more than people saying, "Just be yourself," or, "Just act however you feel." But that's what I try to do now.

Obviously there are areas in which this totally doesn't work--of course there are things I have a lot of anxiety about, or can't learn how to do with any ease, and there's definitely an element of forcing myself to do things or trying to imitate how someone else would do them. But there's a difference between consciously going against your nature, or trying to play make-believe with yourself, in order to deal with something, and just playing a part all the time. I think there were some times when people would say, "Just be yourself," in a way that was super disrespectful of who I am; it was like, "Don't react to things in a way that I wouldn't react to them, because to me your reactions look unnatural." But the fact that I used to find "Just be yourself" to be the most ridiculous thing for anyone to say to me, ever, is now kind of hard for me to relate to.

Like 14 months ago, I made this post called I'm a fake person, and in the process of writing it--well, I knew everything that was in it, but actually writing it down made me incredibly depressed. There was just this fact inside me all the time, that I was fake, and I just tried to avoid thinking about it. But now I just don't feel like that thing is there anymore. (The trans aspect of that post is really weird. I think at that time I actually thought that being trans would make me happier than being cis, but that it just wouldn't be practical for me to transition...but now I, like, actually feel like a girl, in an uncomplicated way, which has never been the case before. So maybe feeling "I'm not a girl," for me, was just a way of feeling something else that I don't have to feel anymore, but I don't know.)

I'm not trying to say that everything is baller and in fact some stuff is much, much worse since I stopped being a fake person, but I do prefer life this way. And I know I'm not going very much into detail about what being "real" or not having a made-up personality means to me, but it's complicated and it may not even look that different superficially. It just feels incredibly different inside.

Anyway, where I was going with this was probably toward the idea of people being empty or being nothing or having nothing to them, because they're different or because they can't do the things other people can do. I think it's really important to acknowledge the difference between having a self that's not socially acceptable, and actually really not having a self at all. Even if your self does have to change or fake or learn a lot of things, or even if it never is accepted by other people, it does really exist.

It's also important to acknowledge the human being/human doing divide, i.e. the difference between not being able to do something, and not being something. For example, if you can't talk on the phone, and then, through scripting and imitating other people, you become able to talk on the phone--your old self wasn't a nothing that has been replaced by an improved, fake self that can talk on the phone. Your old self was just someone who couldn't talk on the phone.

Whereas now I'm kind of like...seriously?

It's weird to say this because a few years ago I don't think there was anything I hated more than people saying, "Just be yourself," or, "Just act however you feel." But that's what I try to do now.

Obviously there are areas in which this totally doesn't work--of course there are things I have a lot of anxiety about, or can't learn how to do with any ease, and there's definitely an element of forcing myself to do things or trying to imitate how someone else would do them. But there's a difference between consciously going against your nature, or trying to play make-believe with yourself, in order to deal with something, and just playing a part all the time. I think there were some times when people would say, "Just be yourself," in a way that was super disrespectful of who I am; it was like, "Don't react to things in a way that I wouldn't react to them, because to me your reactions look unnatural." But the fact that I used to find "Just be yourself" to be the most ridiculous thing for anyone to say to me, ever, is now kind of hard for me to relate to.

Like 14 months ago, I made this post called I'm a fake person, and in the process of writing it--well, I knew everything that was in it, but actually writing it down made me incredibly depressed. There was just this fact inside me all the time, that I was fake, and I just tried to avoid thinking about it. But now I just don't feel like that thing is there anymore. (The trans aspect of that post is really weird. I think at that time I actually thought that being trans would make me happier than being cis, but that it just wouldn't be practical for me to transition...but now I, like, actually feel like a girl, in an uncomplicated way, which has never been the case before. So maybe feeling "I'm not a girl," for me, was just a way of feeling something else that I don't have to feel anymore, but I don't know.)

I'm not trying to say that everything is baller and in fact some stuff is much, much worse since I stopped being a fake person, but I do prefer life this way. And I know I'm not going very much into detail about what being "real" or not having a made-up personality means to me, but it's complicated and it may not even look that different superficially. It just feels incredibly different inside.

Anyway, where I was going with this was probably toward the idea of people being empty or being nothing or having nothing to them, because they're different or because they can't do the things other people can do. I think it's really important to acknowledge the difference between having a self that's not socially acceptable, and actually really not having a self at all. Even if your self does have to change or fake or learn a lot of things, or even if it never is accepted by other people, it does really exist.

It's also important to acknowledge the human being/human doing divide, i.e. the difference between not being able to do something, and not being something. For example, if you can't talk on the phone, and then, through scripting and imitating other people, you become able to talk on the phone--your old self wasn't a nothing that has been replaced by an improved, fake self that can talk on the phone. Your old self was just someone who couldn't talk on the phone.

19 December, 2010

So I just remembered something about the movie Legally Blonde, which is the kind of movie that you end up seeing multiple times at birthday parties and stuff when you're a kid, but the first time I saw it was in theaters with my mom, so I would have been twelve. There's a character in the movie, who according to Google is named Enid, who probably talks two or three times that I can remember. This character is a stereotypical lesbian feminist and all her lines are about that. I think there's also a deleted scene where she argues with the main character about the case while eating with a fork out of a plastic container.

The reason I remember this is because I actually thought it was cool to talk while eating with a fork out a plastic container, as a result of seeing the movie. Also I thought that the line "I single-handedly organized the march for Lesbians Against Drunk Driving" was super funny, even though it's not really a joke, it's just supposed to explain that Enid is a lesbian. I would even quote it.

The reason I'm telling you this is that I was thinking about how if you're a minority and you are unfortunately saddled with the desire to consume pop culture (and am I ever), a lot of the time you have to choose between getting attached to some really dumb character just because you're excited to see someone who belongs to your group, or just giving up on finding any characters who that part of you can identify with. Which is sort of okay when you're older, and besides as you get older you can find movies and TV shows that are less mainstream--but in retrospect it is so, so weird when you're a kid.

The reason I remember this is because I actually thought it was cool to talk while eating with a fork out a plastic container, as a result of seeing the movie. Also I thought that the line "I single-handedly organized the march for Lesbians Against Drunk Driving" was super funny, even though it's not really a joke, it's just supposed to explain that Enid is a lesbian. I would even quote it.

The reason I'm telling you this is that I was thinking about how if you're a minority and you are unfortunately saddled with the desire to consume pop culture (and am I ever), a lot of the time you have to choose between getting attached to some really dumb character just because you're excited to see someone who belongs to your group, or just giving up on finding any characters who that part of you can identify with. Which is sort of okay when you're older, and besides as you get older you can find movies and TV shows that are less mainstream--but in retrospect it is so, so weird when you're a kid.

18 December, 2010

this is pretty great:

http://transmasculinedouchebag.wordpress.com

(sometimes I wonder if it's fucked up for me to find this so hilarious, since as a cis person I obviously have privilege that trans guys don't have, and maybe making fun of trans guys for this kind of thing is something that only trans women should be doing. thoughts?

but I just think that blog is a DELIGHT. And I especially love that one post that someone linked to--which is unfortunately not a joke--that's a guy who goes to Smith saying that people are transphobic for being surprised that he goes to Smith when he's a guy. Yeah. Awesome.)

*this is a parody--maybe I was just primed to know that because of the lj community that I found it in. but sorry if that's not clear.

http://transmasculinedouchebag.wordpress.com

(sometimes I wonder if it's fucked up for me to find this so hilarious, since as a cis person I obviously have privilege that trans guys don't have, and maybe making fun of trans guys for this kind of thing is something that only trans women should be doing. thoughts?

but I just think that blog is a DELIGHT. And I especially love that one post that someone linked to--which is unfortunately not a joke--that's a guy who goes to Smith saying that people are transphobic for being surprised that he goes to Smith when he's a guy. Yeah. Awesome.)

*this is a parody--maybe I was just primed to know that because of the lj community that I found it in. but sorry if that's not clear.

16 December, 2010

something else about Skins

(stfu you can't imagine how much I love this show)

in 3x04 when Freddie finds JJ at Pandora's party and looks after him--I generally hate Freddie, but he's really sweet in that scene. and the whole fact that Freddie, Cook, and JJ all use the phrase "locked on" to refer to instances when JJ becomes obsessively upset; then people who aren't in the trio, like Emily, also start using the phrase about JJ when he is upset.

I think this is cool for multiple reasons.

We eventually learn that JJ has a diagnosis of "lower autism spectrum" (is this really what they say in the UK?). But the truth is, we really don't need a word to tell us about JJ. Often, pop culture portrayals of verbal people with ASD are very superficial and behavioral. It's hard to explain what I mean by behavioral, but you'll just have to take my word for it that JJ isn't portrayed like that. It's something like...you could watch a lot of clips of the show and not realize that JJ is written and played as having autism. But those moments of his character aren't at odds with the moments in between, where he certainly seems like an unusual person but it could be a lot of things, or the moments when he's quite stereotypically (but not inaccurately) "locked on" or having a meltdown.

He's just himself, the whole time.

As far as we know (well, I'm only seven episodes in, but still, that's a lot) none of JJ's friends know about his diagnosis. I'm guessing Freddie and Cook probably do, but we're not actually told that. The only time words related to ASD have been used are a)when we learn JJ's diagnosis by seeing his diagnostic papers and articles on autism that his mother has, and b)when JJ is upset and calls himself a bunch of slurs: "Retard! Nutjob, headcase, spazzo, mong, autistic fucking fruitcake, mental basket, shitty, in a fucking cuckoo's nest."

The first instance is kind of cheesy forced exposition, but the second is really interesting because we get a sense of autism not by itself, but as part of a whole group of stigmatized conditions. I think it's really--well, I can't say it's more realistic for everyone, but personally, I think that, assuming you're not part of any kind of Autistic culture, and especially if you are really upset about your disability, it makes sense that you wouldn't really identify as having "autism" or "Asperger's" or "ASD," but just as Not Being Normal. After all the idea of abusing someone for being "autistic" is not as established as abuse against people who are "retarded" or "mental baskets." So abuse against people with ASD is often done in the name of another disability that ASD superficially resembles. And therefore, it's not really strange that almost every term JJ uses in his outburst is a derogatory term for people with either psychiatric or intellectual disabilities, except for "spazzo," which I think is generally an insult based on CP and/or epilepsy; "autistic;" and "shitty."

Anyway, where I'm going with this, and with the fact that none of the other characters so far have ever had a discussion about JJ having "autism" or "lower autism spectrum" or "Asperger's," or whatever...is that the tendency to repeat a bunch of diagnostic labels in fiction, or to have a character who constantly "acts autistic," is often done in a clumsy attempt to educate, or to sensationalize the disability. In real life, people with ASD, and the people around us, don't usually behave like this.

The risk is, though, that if an ASD fictional character just behaves like themselves and isn't stereotypically, classically ASD all the time, and we don't use the word much, then consumers may just say, "Oh, I didn't realize he was supposed to be autistic, and he was just a little weird anyway. It didn't seem to really affect him." Which is annoying, because the character isn't really making a difference then. Plus there's the whole sense that if someone's ASD isn't immediately visible to you, then it's not really affecting them. But how do you show effects that aren't as obvious as a monologue or something?

What I think is really lovely in Skins is that JJ's disabled-ness is kind of like a ghost--although it's not something that people intentionally don't mention, like a ghost, but it's just something that everyone is very used to and doesn't state outright most of the time, and it's also something that isn't always apparent.

JJ has two best friends. This already takes him away from the worst of autism pop culture, where he would often be portrayed with no friends. But we soon see that there is something strange in the way Freddie and Cook treat JJ. They say some things to him that are kind of harsh, when he's being genuine ("She's not looking at you"). Cook roughhouses with JJ in a way JJ doesn't seem super thrilled by. JJ seems obligated to go along with all of Cook's plans*. There's an element of bullying in the way the two of them treat him, like he inherently has less authority or less value. At the same time we see Freddie and Cook's tenderness and sense of responsibility toward JJ when he is distraught.

(*I should note that there are some times when Freddie starts asking JJ to keep Cook out of trouble; the relationship between the three of them is certainly not a one-dimensional thing where Freddie and Cook always control, bully, and take care of JJ, but I think that's a very strong element.)

This is a really fantastically realistic and complicated portrayal of a trio of teenage friends, regardless of the disability aspect. But with the disability it becomes almost miraculous. Without the help of words like autistic or disabled (although Cook uses some words related to mental illness), we get the picture: JJ is guileless--which makes him funny, and easy to use--and afraid to stand up for himself, because he sees himself as inferior to other people--which, again, makes him easy to use and push around. He is very loyal to his friends, partly because he doesn't like things to change and partly, I think, because he doubts his ability to make new friends. Freddie and Cook sometimes treat him in a way that's really patronizing and disrespectful. (And despite this fucked up stuff, all three genuinely care about each other, because in real life friends can treat each other terribly without meaning harm.)

We also see that JJ feels guilty because his mom is stressed out about him. Which is really classic disabled kid stuff--real disabled kid, not TV disabled kid--and is conveyed really briefly and effectively.

So we kind of see JJ's disabled-ness, or what it means to him socially at least, through the way Cook and Freddie treat him and the way he reacts; and the way he feels guilty about his mom, and sometimes hates himself for looking like all those words. We definitely see straight-up impairment. But sometimes we see how the experience of growing up as disabled--not specifically ASD, but you know, "spazzo, headcase, fruitcake, retard"--has in some ways really shut down JJ's sense of what he can be and what he's allowed to pursue.

Also--the scene that started this for me, at the party, with JJ getting locked on. Freddie comes to the party, finds JJ, helps him to come outside, and then tells off Effy for not looking after JJ; and Effy apologizes. What I was originally just going to say is that Freddie and Effy are both talking about JJ as someone who needs this particular kind of support, but they're not using any words that are explicitly related to disability. Which is just an example of something that I like and think is realistic.

But another thing is just the complicated thing of being disabled and having friends who don't seem to need as much support as you need. To paraphrase, for the third time on this blog, a line from my favorite book: "They needed to treat him like an autistic person, but they also needed not to treat him that way." How is JJ supposed to say that Freddie's pissing him off and needs to stop ruffling his hair, when JJ was dependent on Freddie to come and rescue him from the party? Thinking about this really kills me. Gosh (oh my giddy giddy giddy aunt?) I love television.

ETA: Really annoyed with JJ's portryal in 3x09 though.

in 3x04 when Freddie finds JJ at Pandora's party and looks after him--I generally hate Freddie, but he's really sweet in that scene. and the whole fact that Freddie, Cook, and JJ all use the phrase "locked on" to refer to instances when JJ becomes obsessively upset; then people who aren't in the trio, like Emily, also start using the phrase about JJ when he is upset.

I think this is cool for multiple reasons.

We eventually learn that JJ has a diagnosis of "lower autism spectrum" (is this really what they say in the UK?). But the truth is, we really don't need a word to tell us about JJ. Often, pop culture portrayals of verbal people with ASD are very superficial and behavioral. It's hard to explain what I mean by behavioral, but you'll just have to take my word for it that JJ isn't portrayed like that. It's something like...you could watch a lot of clips of the show and not realize that JJ is written and played as having autism. But those moments of his character aren't at odds with the moments in between, where he certainly seems like an unusual person but it could be a lot of things, or the moments when he's quite stereotypically (but not inaccurately) "locked on" or having a meltdown.

He's just himself, the whole time.

As far as we know (well, I'm only seven episodes in, but still, that's a lot) none of JJ's friends know about his diagnosis. I'm guessing Freddie and Cook probably do, but we're not actually told that. The only time words related to ASD have been used are a)when we learn JJ's diagnosis by seeing his diagnostic papers and articles on autism that his mother has, and b)when JJ is upset and calls himself a bunch of slurs: "Retard! Nutjob, headcase, spazzo, mong, autistic fucking fruitcake, mental basket, shitty, in a fucking cuckoo's nest."

The first instance is kind of cheesy forced exposition, but the second is really interesting because we get a sense of autism not by itself, but as part of a whole group of stigmatized conditions. I think it's really--well, I can't say it's more realistic for everyone, but personally, I think that, assuming you're not part of any kind of Autistic culture, and especially if you are really upset about your disability, it makes sense that you wouldn't really identify as having "autism" or "Asperger's" or "ASD," but just as Not Being Normal. After all the idea of abusing someone for being "autistic" is not as established as abuse against people who are "retarded" or "mental baskets." So abuse against people with ASD is often done in the name of another disability that ASD superficially resembles. And therefore, it's not really strange that almost every term JJ uses in his outburst is a derogatory term for people with either psychiatric or intellectual disabilities, except for "spazzo," which I think is generally an insult based on CP and/or epilepsy; "autistic;" and "shitty."

Anyway, where I'm going with this, and with the fact that none of the other characters so far have ever had a discussion about JJ having "autism" or "lower autism spectrum" or "Asperger's," or whatever...is that the tendency to repeat a bunch of diagnostic labels in fiction, or to have a character who constantly "acts autistic," is often done in a clumsy attempt to educate, or to sensationalize the disability. In real life, people with ASD, and the people around us, don't usually behave like this.

The risk is, though, that if an ASD fictional character just behaves like themselves and isn't stereotypically, classically ASD all the time, and we don't use the word much, then consumers may just say, "Oh, I didn't realize he was supposed to be autistic, and he was just a little weird anyway. It didn't seem to really affect him." Which is annoying, because the character isn't really making a difference then. Plus there's the whole sense that if someone's ASD isn't immediately visible to you, then it's not really affecting them. But how do you show effects that aren't as obvious as a monologue or something?

What I think is really lovely in Skins is that JJ's disabled-ness is kind of like a ghost--although it's not something that people intentionally don't mention, like a ghost, but it's just something that everyone is very used to and doesn't state outright most of the time, and it's also something that isn't always apparent.

JJ has two best friends. This already takes him away from the worst of autism pop culture, where he would often be portrayed with no friends. But we soon see that there is something strange in the way Freddie and Cook treat JJ. They say some things to him that are kind of harsh, when he's being genuine ("She's not looking at you"). Cook roughhouses with JJ in a way JJ doesn't seem super thrilled by. JJ seems obligated to go along with all of Cook's plans*. There's an element of bullying in the way the two of them treat him, like he inherently has less authority or less value. At the same time we see Freddie and Cook's tenderness and sense of responsibility toward JJ when he is distraught.

(*I should note that there are some times when Freddie starts asking JJ to keep Cook out of trouble; the relationship between the three of them is certainly not a one-dimensional thing where Freddie and Cook always control, bully, and take care of JJ, but I think that's a very strong element.)

This is a really fantastically realistic and complicated portrayal of a trio of teenage friends, regardless of the disability aspect. But with the disability it becomes almost miraculous. Without the help of words like autistic or disabled (although Cook uses some words related to mental illness), we get the picture: JJ is guileless--which makes him funny, and easy to use--and afraid to stand up for himself, because he sees himself as inferior to other people--which, again, makes him easy to use and push around. He is very loyal to his friends, partly because he doesn't like things to change and partly, I think, because he doubts his ability to make new friends. Freddie and Cook sometimes treat him in a way that's really patronizing and disrespectful. (And despite this fucked up stuff, all three genuinely care about each other, because in real life friends can treat each other terribly without meaning harm.)

We also see that JJ feels guilty because his mom is stressed out about him. Which is really classic disabled kid stuff--real disabled kid, not TV disabled kid--and is conveyed really briefly and effectively.

So we kind of see JJ's disabled-ness, or what it means to him socially at least, through the way Cook and Freddie treat him and the way he reacts; and the way he feels guilty about his mom, and sometimes hates himself for looking like all those words. We definitely see straight-up impairment. But sometimes we see how the experience of growing up as disabled--not specifically ASD, but you know, "spazzo, headcase, fruitcake, retard"--has in some ways really shut down JJ's sense of what he can be and what he's allowed to pursue.

Also--the scene that started this for me, at the party, with JJ getting locked on. Freddie comes to the party, finds JJ, helps him to come outside, and then tells off Effy for not looking after JJ; and Effy apologizes. What I was originally just going to say is that Freddie and Effy are both talking about JJ as someone who needs this particular kind of support, but they're not using any words that are explicitly related to disability. Which is just an example of something that I like and think is realistic.

But another thing is just the complicated thing of being disabled and having friends who don't seem to need as much support as you need. To paraphrase, for the third time on this blog, a line from my favorite book: "They needed to treat him like an autistic person, but they also needed not to treat him that way." How is JJ supposed to say that Freddie's pissing him off and needs to stop ruffling his hair, when JJ was dependent on Freddie to come and rescue him from the party? Thinking about this really kills me. Gosh (oh my giddy giddy giddy aunt?) I love television.

ETA: Really annoyed with JJ's portryal in 3x09 though.

14 December, 2010

all it takes

Tonight in line at the dining hall I was having a conversation with someone I kind of know. He was strikingly knowledgeable about when, in the mind of the register at the dining hall, the "dinner" period becomes the "fourth meal" period. Many people aren't clear on this, and when I am cashiering people will sometimes try to swipe their card at 9:30 after eating dinner at 5:30, not understanding that it is still the dinner period and their card won't work again until 10:01 when fourth meal officially starts.

So I was like, "Wait did you cashier at some point?" and he said, "No, but when I was a freshman I lived in the dorm in this building so I was here a lot," and I was like, "Dude I know that, we lived on the same floor," and he said, "Oh sorry, I remember." But as soon as I thought about it, I felt much sorrier than he did.

This guy (whose real speech style I am not even attempting to replicate) has ASD and Tourette's. He is probably everyone's stereotype of a person with "Asperger's"--I mean, now I think the unusualness of his speech is what's most obvious, but when we were freshmen he would always monologue about engines--isn't that the most stereotypical thing you can think of? He'd draw pictures of machines and explain them to people, for heaven's sake!

The way I treated him was just...barf. I was always trying to tell him what to do and how to talk to other people. He didn't get mad at me for this, but he'd never asked me to do it. I just couldn't help thinking that I knew something he didn't. I knew the proper way to act if you had ASD. You were careful. You never talked about anything you were interested in. And look, look, some people were ignoring him when he talked! I was right. Why didn't he just pick up on what I was trying to teach him so he could make more friends?

Except, then he did make a lot of friends, and became really popular. I hardly ever see him alone. He's involved in lots of extracurricular activities. Most people don't guess that he has ASD because he doesn't fit into their idea of it; he's not ~isolated~ by his ~pathology~. He's just himself, and almost everyone likes him for it.

I haven't spent a lot of time with this guy since the first semester of our first year. But being in school with him, and seeing how things turned out, was one of the things that made my frame on social skills begin to change. He is fine. He did not need help becoming more like me as I was then, or more like anyone else.

What's so important is that all it takes is to see one or two really naturally, visibly nonstandard people in a state of really awesome social success.

You stop chewing on your tongue while the person is talking, thinking about what they should be like, what they probably just don't understand is the right way to be; you stop cringing for what's going to happen to them if they're not careful. You just see the person. You see that they're really cool. You see that you weren't treating them like an adult, before.

And then you think about all the environments where the way this person is would sentence them to isolation, bullying, unemployment, and other undesirable ends, because of their "bad social skills." And then you start to see how incredibly cruel and ridiculous those environments are, for being the way they are. And then you stop being careful. And you start being super pissed off.

So I was like, "Wait did you cashier at some point?" and he said, "No, but when I was a freshman I lived in the dorm in this building so I was here a lot," and I was like, "Dude I know that, we lived on the same floor," and he said, "Oh sorry, I remember." But as soon as I thought about it, I felt much sorrier than he did.

This guy (whose real speech style I am not even attempting to replicate) has ASD and Tourette's. He is probably everyone's stereotype of a person with "Asperger's"--I mean, now I think the unusualness of his speech is what's most obvious, but when we were freshmen he would always monologue about engines--isn't that the most stereotypical thing you can think of? He'd draw pictures of machines and explain them to people, for heaven's sake!

The way I treated him was just...barf. I was always trying to tell him what to do and how to talk to other people. He didn't get mad at me for this, but he'd never asked me to do it. I just couldn't help thinking that I knew something he didn't. I knew the proper way to act if you had ASD. You were careful. You never talked about anything you were interested in. And look, look, some people were ignoring him when he talked! I was right. Why didn't he just pick up on what I was trying to teach him so he could make more friends?

Except, then he did make a lot of friends, and became really popular. I hardly ever see him alone. He's involved in lots of extracurricular activities. Most people don't guess that he has ASD because he doesn't fit into their idea of it; he's not ~isolated~ by his ~pathology~. He's just himself, and almost everyone likes him for it.

I haven't spent a lot of time with this guy since the first semester of our first year. But being in school with him, and seeing how things turned out, was one of the things that made my frame on social skills begin to change. He is fine. He did not need help becoming more like me as I was then, or more like anyone else.

What's so important is that all it takes is to see one or two really naturally, visibly nonstandard people in a state of really awesome social success.

You stop chewing on your tongue while the person is talking, thinking about what they should be like, what they probably just don't understand is the right way to be; you stop cringing for what's going to happen to them if they're not careful. You just see the person. You see that they're really cool. You see that you weren't treating them like an adult, before.

And then you think about all the environments where the way this person is would sentence them to isolation, bullying, unemployment, and other undesirable ends, because of their "bad social skills." And then you start to see how incredibly cruel and ridiculous those environments are, for being the way they are. And then you stop being careful. And you start being super pissed off.

12 December, 2010

in cheerier news, though

can I just say how AMAZING this was?

but I'm sad because Emma Bell is really cute.

but I'm sad because Emma Bell is really cute.

This isn't really complete and it's like 3 posts in one

Hi, kids. Today I want to talk about sadness and rage. Or basically any related emotion or combination of the two that causes the people around you to be uncomfortable. An easy way to talk about this is by talking about Autism Every Day, which has been beaten to within an inch of its life, and I certainly don't have anything new to say about it, but look at this:

This is the title card of the movie, which as you know is basically a propaganda piece about how hard it is to live with someone who has autism. If I remember right, the movie features montages of young people with autism crying and screaming.

A friend of mine, who is usually pretty social-justice-y and good on disability stuff, watched this movie for the first time, and after watching about a minute of it, she said, "Wow, I didn't know autism was this bad, maybe I wouldn't be able to handle this either if I was a parent." And I felt sad that she had this response, because to me the portrayal of emotion in this movie is very obviously incredibly slanted.

Because here we have a picture of a girl crying being used to prove that people like this girl should not exist. We basically have someone's emotions being used to devalue her. And to me, it's very obvious how emotions mean completely different things depending on the privilege or the role of the person showing emotion.

If you see the family member of someone who's identified as "the disabled person" expressing emotion--crying, screaming, expressing that they want to kill themselves or kill someone else, seeming very annoyed about something pretty small like not being able to go out to lunch--this is taken of evidence of how wronged the person is by the disability that "the disabled person" has (which, I'm sorry, is not that different from saying they are wronged by "the disabled person," straight up).

For the record, I should say that I don't have any problem with the one mother in Autism Every Day complaining that she can't go out to lunch--I don't think she's being petty or something, I think it's something that represents, to her, how much pressure she's under. What I do have a problem with is that if "the disabled person" complained about something small like not being able to go out to lunch, it would probably be used to show that "the disabled person" is unreasonable. And definitely in the cases of crying, screaming, and verbally or physically showing an interest in violence against oneself or others, "the disabled person" cannot do these things without showing how undesirable their disability is, or how unbearable they are.

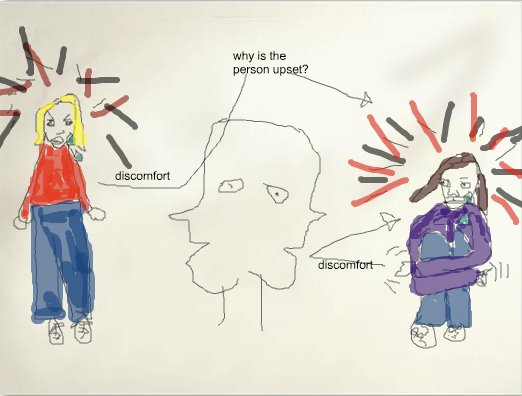

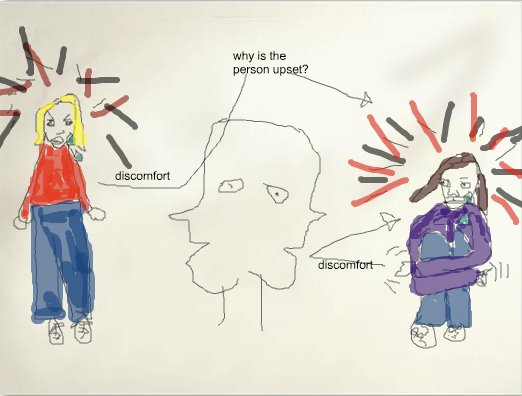

So if you have privilege, when you show emotion that causes discomfort in someone else, it just shows that your life sucks, and turns the viewer's discomfort toward the cause that you want to promote. If you don't have privilege, and you show the same emotion, the viewer's discomfort stays with you and is turned back towards you. I made this swell picture at artpad showing how to respond when a family member of "the disabled person" is upset to a degree that makes you uncomfortable, vs. how you should respond if "the disabled person" herself is upset.

This is sure to turn out really well for everyone except the disabled person.

Someone in my family who I'm very close with has a mental health condition and I know they don't want people to know about it. But it is also very hard for me not to write about it, because in retrospect I can really see how it fits into "the disabled person" vs. family member in terms of expression of emotion. (I'm talking about this in the past tense, somewhat disingenuously, but whatever.)

I was seen as "the disabled person," while this other person wasn't. And it only became apparent to me fairly recently that I, and another family member, who regularly experienced this person screaming and crying at us, didn't just deserve this because of the way we were.

I wasn't nice always. Sometimes I felt threatened and would hit or shove the person to get them out of my space. If we were having a conflict, I would sometimes get really upset and say things that I knew were hurtful. Sometimes I was sad about things that were going on, and I cried, which caused the person to be upset.

However, I've eventually come to realize the incredible amount of room this person had compared to the amount of room I had. The person could say all kinds of small hurtful things and it wasn't considered wrong for them to do that. If I said anything back, even if I tried to be really diplomatic, what happened next was my fault. If the person cried, it was because I was hurting them. If I cried, I was hurting them by crying. If someone apologized, it was usually me. If someone tried to calm someone else down, it was usually me.

I know, now, that this person can't help being very emotional and sad sometimes, and that what happens is no one's fault. But the person never really sat me down and said, "I have depression. Sometimes things will be scary. It's not your fault." Instead they allowed everything to go into this frame, where the people they cried and yelled at had brought on this reaction by not having certain abilities. This is the only thing I resent them for, not the actual crying.

Sometimes I think that my whole interest in anti-ableism just comes out of growing up this way.

But the reason I wanted to write this in the first place is because I have this really good friend. Let's call him K. It feels like every few times I hang out with K, I end up not only crying really hard and talking about every sad thing I can think of, but I actually say mean things to K and accuse him of not caring about me. K gets upset by this, of course, and wonders if he's a bad friend. I feel bad because I'm putting the huge emotional burden of these conversations on him--but I can't seem to stop.

Today, I started trying to write K an email apologizing and telling him that he really isn't a bad friend at all. Then I started trying to explain why I treat him this way, if I don't think he's a bad friend. I ended up realizing that the reason I get so angry and difficult is that I know nothing bad will happen; K won't be mad at me long-term, he won't stop being friends with me, he won't hate me. When I'm with him, I have a safe place to get upset.

Obviously this is a problem, since I don't want to punish people for making me feel safe. But it made me think about how anger and sadness can kind of be a privilege. We think of crying really hard as being an undesirable experience. But really, the ability to cry really hard and not have it be used against you means that you have power. You have so much control if even losing control doesn't matter.

This is the title card of the movie, which as you know is basically a propaganda piece about how hard it is to live with someone who has autism. If I remember right, the movie features montages of young people with autism crying and screaming.

A friend of mine, who is usually pretty social-justice-y and good on disability stuff, watched this movie for the first time, and after watching about a minute of it, she said, "Wow, I didn't know autism was this bad, maybe I wouldn't be able to handle this either if I was a parent." And I felt sad that she had this response, because to me the portrayal of emotion in this movie is very obviously incredibly slanted.

Because here we have a picture of a girl crying being used to prove that people like this girl should not exist. We basically have someone's emotions being used to devalue her. And to me, it's very obvious how emotions mean completely different things depending on the privilege or the role of the person showing emotion.

If you see the family member of someone who's identified as "the disabled person" expressing emotion--crying, screaming, expressing that they want to kill themselves or kill someone else, seeming very annoyed about something pretty small like not being able to go out to lunch--this is taken of evidence of how wronged the person is by the disability that "the disabled person" has (which, I'm sorry, is not that different from saying they are wronged by "the disabled person," straight up).

For the record, I should say that I don't have any problem with the one mother in Autism Every Day complaining that she can't go out to lunch--I don't think she's being petty or something, I think it's something that represents, to her, how much pressure she's under. What I do have a problem with is that if "the disabled person" complained about something small like not being able to go out to lunch, it would probably be used to show that "the disabled person" is unreasonable. And definitely in the cases of crying, screaming, and verbally or physically showing an interest in violence against oneself or others, "the disabled person" cannot do these things without showing how undesirable their disability is, or how unbearable they are.

So if you have privilege, when you show emotion that causes discomfort in someone else, it just shows that your life sucks, and turns the viewer's discomfort toward the cause that you want to promote. If you don't have privilege, and you show the same emotion, the viewer's discomfort stays with you and is turned back towards you. I made this swell picture at artpad showing how to respond when a family member of "the disabled person" is upset to a degree that makes you uncomfortable, vs. how you should respond if "the disabled person" herself is upset.

This is sure to turn out really well for everyone except the disabled person.

Someone in my family who I'm very close with has a mental health condition and I know they don't want people to know about it. But it is also very hard for me not to write about it, because in retrospect I can really see how it fits into "the disabled person" vs. family member in terms of expression of emotion. (I'm talking about this in the past tense, somewhat disingenuously, but whatever.)

I was seen as "the disabled person," while this other person wasn't. And it only became apparent to me fairly recently that I, and another family member, who regularly experienced this person screaming and crying at us, didn't just deserve this because of the way we were.

I wasn't nice always. Sometimes I felt threatened and would hit or shove the person to get them out of my space. If we were having a conflict, I would sometimes get really upset and say things that I knew were hurtful. Sometimes I was sad about things that were going on, and I cried, which caused the person to be upset.

However, I've eventually come to realize the incredible amount of room this person had compared to the amount of room I had. The person could say all kinds of small hurtful things and it wasn't considered wrong for them to do that. If I said anything back, even if I tried to be really diplomatic, what happened next was my fault. If the person cried, it was because I was hurting them. If I cried, I was hurting them by crying. If someone apologized, it was usually me. If someone tried to calm someone else down, it was usually me.

I know, now, that this person can't help being very emotional and sad sometimes, and that what happens is no one's fault. But the person never really sat me down and said, "I have depression. Sometimes things will be scary. It's not your fault." Instead they allowed everything to go into this frame, where the people they cried and yelled at had brought on this reaction by not having certain abilities. This is the only thing I resent them for, not the actual crying.

Sometimes I think that my whole interest in anti-ableism just comes out of growing up this way.

But the reason I wanted to write this in the first place is because I have this really good friend. Let's call him K. It feels like every few times I hang out with K, I end up not only crying really hard and talking about every sad thing I can think of, but I actually say mean things to K and accuse him of not caring about me. K gets upset by this, of course, and wonders if he's a bad friend. I feel bad because I'm putting the huge emotional burden of these conversations on him--but I can't seem to stop.

Today, I started trying to write K an email apologizing and telling him that he really isn't a bad friend at all. Then I started trying to explain why I treat him this way, if I don't think he's a bad friend. I ended up realizing that the reason I get so angry and difficult is that I know nothing bad will happen; K won't be mad at me long-term, he won't stop being friends with me, he won't hate me. When I'm with him, I have a safe place to get upset.

Obviously this is a problem, since I don't want to punish people for making me feel safe. But it made me think about how anger and sadness can kind of be a privilege. We think of crying really hard as being an undesirable experience. But really, the ability to cry really hard and not have it be used against you means that you have power. You have so much control if even losing control doesn't matter.

so I made the best Privilege Denying Dude ever and only FOUR PEOPLE on the Internet liked it. And one of them was my friend who saw me complaining on Facebook about how no one liked it.

I'm seriously sad.

10 December, 2010

I watched this Skins episode and had some gay thoughts and some Autistic thoughts

So for a really long time I've been wanting to watch Skins because I knew the following information: there was this lesbian couple that everyone liked. And then one of them had sex with a guy with ASD because she felt sorry for him, and all the lesbians on the Internet were mad because it was like she was really straight! Argh! And hearing this, I was kind of like, gosh that's fucked up for the guy with ASD though. What about him? Queer Autistic TV investigation time!

So, I watched the episode where the lesbian sleeps with the guy with autism. And it was like...I actually can't believe it exists. The character with autism is the best fictional character with ASD I've ever read about or seen. It's so easy to explain why something is wrong, and so hard to explain why something is right, so I almost don't even know how to talk about why I love him so much. (Spoilers, obviously.)

The walls of his bedroom are covered with a chart he made about his relationships with other people. And that sounds so stupid and offensive, but somehow it's not. And he walks like he has ASD and he talks like he has ASD; like, the real kind, not the TV kind. And and and...I just can't even talk about it. I'll probably end up watching the entire show and then maybe I can try to write about him again.

It was such a good episode though. Like the wall chart, the "once-only charity event" sex wasn't as offensive as it sounds. Towards the beginning of the episode, JJ says something like, "If I could be normal for one day I'd lose my virginity, and then I'd tell my friends not to fight with each other and they'd listen to me instead of ruffling my hair." Emily (the lesbian character) replies that maybe he could have the things he wants if he actually pursued them. So he sets out to tell his friends what he thinks of them, with terrible results, but in the process he and Emily become closer and she announces that they should sleep together. It's not like, "I'm going to have sex with you because no one else would ever have sex with you," it's like, "I'm going to have sex with you because you think that you'll never have sex, and this will change the way you think of yourself." Which is kind of a messed up reason to have sex with someone, but it's not insulting. (And apparently he later has a real relationship.)

The episode ends with JJ's mom watching the two friends talking and laughing together, and realizing that she doesn't need to worry about him--which was one of the things he most wanted. And then I almost cried. It was so good. I just like, couldn't even handle it, from a gay or an Autistic perspective. Emily and JJ were, like, humans!

Like, if I can put on my other hat--as a person who's gay in a weird way--I really appreciated this. I feel like if people think a lesbian sleeping with men is just inherently offensive no matter what, then they don't understand what's so offensive about most "lesbians sleeping with men" plotlines. I feel like the problem is the implication that men trump women--so women can be involved with women, have sex or even a relationship, and they can even identify as gay or bi--but a guy can change everything, or a guy is the root of everything. For example, my understanding is that on House a female character was having sex with random women because she was depressed, and afraid of a relationship with a guy she liked. This obviously devalues sex/relationships between women because it's just presented as something you do, not something important like heterosexual relationships.

But what happens on Skins is basically the opposite of this. Emily is in love with a girl, she has sex with JJ as a gesture of friendship, and at the end of the episode she's still in love with her girlfriend. It shows that lesbian feelings can be secure and stable and aren't completely dislodged the minute you get the chance to sleep with a guy.

Like, I guess I'm gold star because I've never had sex with a guy, but I feel very un-gold star sometimes because I've had so many really close, affectionate friendships with guys, which have sometimes had a sexual dimension. These guys have always thought of me as gay and I've always known when involved in these friendships that if I get married I want it to be to a woman, and that when I'm sexually moved by something involving a guy, it's in spite of the fact that he's a guy which tends to mean my reactions are weaker.

To try to explain the sex thing without being too explicit, guys are like a bunch of grapes or some Easy Mac or something. I mean I love Easy Mac, but it's not a whole meal. And I don't think the fact that guys are sexual Easy Mac to me (instead of some disgusting food that I would never eat in any circumstances) makes me any less of a lesbian. I'm sorry but it's completely heterosexist to say that my feelings towards guys are on the same level as my feelings towards girls. If you say that, it's like you're saying men are just so super important that the weight of anything involving men gets multiplied by a billion so that it automatically outweighs anything involving just women.

Yeah so anyway I really liked this episode of Skins and I think it's awesome that they showed a lesbian doing stuff with a guy and still very much being a lesbian. And it was the Best Autism Ever. And I'm excited to watch more.

So, I watched the episode where the lesbian sleeps with the guy with autism. And it was like...I actually can't believe it exists. The character with autism is the best fictional character with ASD I've ever read about or seen. It's so easy to explain why something is wrong, and so hard to explain why something is right, so I almost don't even know how to talk about why I love him so much. (Spoilers, obviously.)

The walls of his bedroom are covered with a chart he made about his relationships with other people. And that sounds so stupid and offensive, but somehow it's not. And he walks like he has ASD and he talks like he has ASD; like, the real kind, not the TV kind. And and and...I just can't even talk about it. I'll probably end up watching the entire show and then maybe I can try to write about him again.

It was such a good episode though. Like the wall chart, the "once-only charity event" sex wasn't as offensive as it sounds. Towards the beginning of the episode, JJ says something like, "If I could be normal for one day I'd lose my virginity, and then I'd tell my friends not to fight with each other and they'd listen to me instead of ruffling my hair." Emily (the lesbian character) replies that maybe he could have the things he wants if he actually pursued them. So he sets out to tell his friends what he thinks of them, with terrible results, but in the process he and Emily become closer and she announces that they should sleep together. It's not like, "I'm going to have sex with you because no one else would ever have sex with you," it's like, "I'm going to have sex with you because you think that you'll never have sex, and this will change the way you think of yourself." Which is kind of a messed up reason to have sex with someone, but it's not insulting. (And apparently he later has a real relationship.)

The episode ends with JJ's mom watching the two friends talking and laughing together, and realizing that she doesn't need to worry about him--which was one of the things he most wanted. And then I almost cried. It was so good. I just like, couldn't even handle it, from a gay or an Autistic perspective. Emily and JJ were, like, humans!

Like, if I can put on my other hat--as a person who's gay in a weird way--I really appreciated this. I feel like if people think a lesbian sleeping with men is just inherently offensive no matter what, then they don't understand what's so offensive about most "lesbians sleeping with men" plotlines. I feel like the problem is the implication that men trump women--so women can be involved with women, have sex or even a relationship, and they can even identify as gay or bi--but a guy can change everything, or a guy is the root of everything. For example, my understanding is that on House a female character was having sex with random women because she was depressed, and afraid of a relationship with a guy she liked. This obviously devalues sex/relationships between women because it's just presented as something you do, not something important like heterosexual relationships.

But what happens on Skins is basically the opposite of this. Emily is in love with a girl, she has sex with JJ as a gesture of friendship, and at the end of the episode she's still in love with her girlfriend. It shows that lesbian feelings can be secure and stable and aren't completely dislodged the minute you get the chance to sleep with a guy.

Like, I guess I'm gold star because I've never had sex with a guy, but I feel very un-gold star sometimes because I've had so many really close, affectionate friendships with guys, which have sometimes had a sexual dimension. These guys have always thought of me as gay and I've always known when involved in these friendships that if I get married I want it to be to a woman, and that when I'm sexually moved by something involving a guy, it's in spite of the fact that he's a guy which tends to mean my reactions are weaker.

To try to explain the sex thing without being too explicit, guys are like a bunch of grapes or some Easy Mac or something. I mean I love Easy Mac, but it's not a whole meal. And I don't think the fact that guys are sexual Easy Mac to me (instead of some disgusting food that I would never eat in any circumstances) makes me any less of a lesbian. I'm sorry but it's completely heterosexist to say that my feelings towards guys are on the same level as my feelings towards girls. If you say that, it's like you're saying men are just so super important that the weight of anything involving men gets multiplied by a billion so that it automatically outweighs anything involving just women.

Yeah so anyway I really liked this episode of Skins and I think it's awesome that they showed a lesbian doing stuff with a guy and still very much being a lesbian. And it was the Best Autism Ever. And I'm excited to watch more.

09 December, 2010

Shelly was still thirteen years old

In 1981, I was employed to teach a sailing course for individuals with disabilities. In an attempt to recruit new students, we visited several segregated living accommodations for people with physical disabilities. When we entered one "facility," I recognized a young woman whom I shall refer to as Shelly. Shelly and I had come to know each other while we were in a segregated public school and had become close friends. She had cerebral palsy. and was an intelligent, perceptive girl who had a dry and biting sense of humor. Together we had talked about what it was like to be handicapped, we laughed about how people reacted to us and shared many of the common ironies and frustrations.

After completing Grade Seven, I was integrated into a regular school and from there continued on into a secondary school, and then entered University. Shelly had continued her education in various segregated settings, eventually moving into a segregated residence. Shelly and I had parted when we were both thirteen years old. I had not seen Shelly for ten years since that time. Consequently, I was overjoyed to see Shelly again. I sat down and began talking with her. In five minutes, I painfully realized that Shelly was still thirteen years old.

At that moment, the connection between segregation and death became apparent.

--Norman Kunc, Integration: Being Realistic Isn't Realistic