He was a kid I met this summer at the school where I interned. I have written about him several times, sometimes at length. And although he was my favorite kid at the school, that isn't why Danny is always surfacing in my mind, tiny in his big t-shirts, flinging himself around and reciting things.

It's through Danny that I found out for sure, this stuff is about me.

Because the first thing people use on us is always, "It's not about you." When I was a kid, when I first started reading about autism rights, it was so instinctive: of course it's wrong to say "cure autism now." Of course it's wrong to say autism is a tragedy, a disease, it's wrong to give kids electric shocks, it's wrong to say you thought about killing your kid in a video about eliminating autistic people from the gene pool. Like Sinclair says it's wrong to mourn for a living person. All this stuff was plain and clear and bright, and I was autistic, and I was being attacked.

Right?

Well, not to anyone else.

Because, of course, if I told anyone I was autistic, they said I was lying, or I had a different kind of autism that made me smart and talented, so I wasn't like Those Kids, the kids who needed to be cured. And that I should think about their parents, about the money and time to care for a person like that, about the dreams that are shattered when your kid is really autistic, not smart autistic, the real kind. So in my late teens when I put myself through my paces, when I figured out my deficiencies and set myself to systematically eradicating them, one of the deficiencies I eradicated was my use of the word autistic. Because you shouldn't use words people don't understand. And you shouldn't use words that will make someone feel bad, someone who has a kid who's Really Bad, Really Disabled. Because you're not that.

And I met some autistic kids and they were not much like me, and I didn't know to apply what I knew about myself to them, because I couldn't see what they were feeling inside. But I liked them. Then I met some people with intellectual disabilities and I liked them too; after a brief nervousness because some of them looked so different from me, and made noises I didn't understand, it was easy to like them. They were people who liked things, some of them the same things I liked. I could see that they weren't on the surface very similar to me, but I liked being around them almost more because of that, because it made me feel happy and chastened to misjudge them again and again. To be proven wrong when I thought I could quantify them just because I knew more words.

So by this point, I was pretty much sold, even if I wasn't Really Autistic, on the idea that people with developmental disabilities matter. Because I was around them all the time and it was obvious they mattered. But still, I felt my position was that of an outsider, an ally. I had opinions but I didn't necessarily feel that I had much right to talk about them; I didn't feel I had as much right as the parents or teachers of people with developmental disabilities.

And then I interned at this school.

And I started out thinking: wow, ABA is so cool. I've heard negative things about it from other Not Really Autistic people, but who am I to talk about what these Really Autistic kids need? They can't even talk. They might bite themselves or something. What the hell do I know about that?

And then I met Danny and the other kids in his class. High-functioning kids. Verbal kids.

Tony, who had been nonverbal a few years before, was incredibly hardworking and sweet. When he went into the school director's office and turned out the lights as a joke, I laughed, but she said, "Tony. Look at my face. How do you think that made me feel?" She stood there looking grim until he apologized.

James was stressed out and upset; one of his teachers leaned towards him, staring fiercely into his eyes, talking with cold, strained-sounding words, the kind of voice I called "static" when I was a kid. James looked scaredly back at her, wriggling his hands around in his lap. "James," she said. "I know you're upset. But what you're doing with your hands looks silly." This boy, all the tension in him being channeled into something harmless, something she had to look under the table to see. His tension was silly. His discomfort was an inconvenience. He was eight or nine years old.

And Danny with his words. "Danny's an interesting kid," the school director told me. "He likes to be in charge." Danny and I were walking, holding hands, and when I responded with concern when he told me he was tired, another teacher told me, "He's playing you." It's true that Danny was a bossy little boy; when we played restaurant, he replied, "No, we're out of that" again and again until I ordered the food he wanted to pretend to make. And his love of subway trains spilled out everywhere. He was supposed to write a story about a sad princess, and he did, but half the story was about the princess's friends taking her on the subway to cheer her up. He was supposed to write a crossword puzzle and the clues were things like, "Transfer is available to _____ North." The school was full of subway maps, since many field trips involved subways, and Danny would sometimes just lean over a desk, pressing his face into the shapes and colors, whispering his favorite schedules to himself.

Danny just liked words. When he was using his special words, the weird words he scrounged for or made up himself, he would find himself jerkily hopping across the room, speaking in a squeaky voice, his small face tense with excitement. "Presentation" was a weird word for movie, "document" was a way to talk about the letter he had typed on the computer for his parents. "I went to the barber," he said when I commented on his newly short hair, and then, with a rush of joy, "but I like to call it the hair shop!"

I like words too. It was hard to watch Danny's teachers nudge him, sit down with him, say, "Danny, the word 'presentation' is a little weird; you need to say 'movie.'" It was hard to watch the way they looked at him, pointedly, until he stilled his hopping and lowered his voice to a more standard pitch. When Danny found out my middle name is Wood, he completely tripped out on it, hammering pretend nails into my stomach and giggling, "I'm gonna build something out of you!" "Danny," a teacher said, "don't be weird. You and Amanda were talking about names."

It was the word weird. Nothing foreign my whole life. Tracing words and shapes in the air, crossing myself, my mom asking me a lot of questions, "Have you been feeling the urge to do that lately? Why do you do that?" with so much static it was clear I'd better keep my hands as still as possible when she was around. Running jerkily up the stairs at school, I couldn't help myself until I was fifteen or sixteen, despite the older boys laughing to each other--"is she trying to race you?" Movement just consumed me that way. And being a thirteen-year-old who said "suppose" and "quite" when no other kids did. Just loving words too much, finding it hard to stay away from the strange ones. And getting too excited. Being weird is not that alien for me.

So my divisions broke down a little, because I was watching a kid just like me, and I was learning, in very specific, qualitative terms, what they thought of people like me. I was so nervous about keeping myself still and using the right words because I thought they wouldn't let me intern there if they knew I was actually like Danny, that I didn't think he was weird at all. All of Danny's teachers had been taught to grimace and say how annoying it was when he talked about trains. They watched The Office, but they never ever laughed when Danny told flat, self-referential jokes on purpose, twisting the ones he had been trained to say. I thought Danny was funny. Every time I talked to him I felt nervous about doing something that his teachers would think was wrong, and I also felt bad about perpetuating the attitude he was being taught, that none of the things he loved mattered.

So from specific to general, from Danny to James and Tony, to Max and John. John's teacher made him walk, in stiff, clean steps, and if he started doing anything that looked like skipping or jumping, she grabbed his arm, said "No," forced him again and again. Max liked to move his arm in circles while he was watching TV, so he was hauled off into an office, pushed down into a chair, had mouthwash forced into his mouth while he cried. They told me they were narrowing it down, he was moving less and less. Max and John didn't talk. James and Tony didn't talk as well as I do. But I move too much, and I move wrong, especially when I was a kid, and in that school I saw what they do to kids who move wrong.

I realized that, actually, a lot of it was about moving wrong. Or talking wrong, if you could talk. Or just taking too much initiative--wanting to make up songs, like Danny did, or playing a practical joke, like Tony did. That these kids looked and acted different and the school wanted to control them and make them as still and docile as they could possibly be. Watching them treat hopping, rocking, and neologisms like you'd treat a bomb on an airplane--it was like being at summer camp with a kid from the south, sitting in a car uncomfortably while he said he'd kill a gay person if they ever came near him. Wanting to say, no, it's not anything important; I'm like that, see? But I didn't talk in the car and I didn't talk in the school.

This is too long. It's hard to even explain it. I just have to say, for the millionth time, that this whole functioning level thing--yes, it matters in certain ways. I can buy and cook food for myself, while a severely autistic person probably can't. I can hide the way I move and talk better than other people can. But this doesn't really have much to do with politics, because when people claim that "cure autism now" and the disease and the Judge Rotenberg Center are not about me, well I beg to differ. The only reason they're not about me is that I'm old and verbal enough to not be vulnerable to that kind of abuse. They would be all too happy to practice it on me if they could. Autistic people do not get abused because they are low-functioning, they get abused because they do weird things.

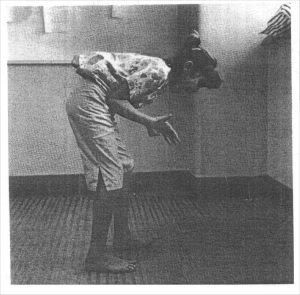

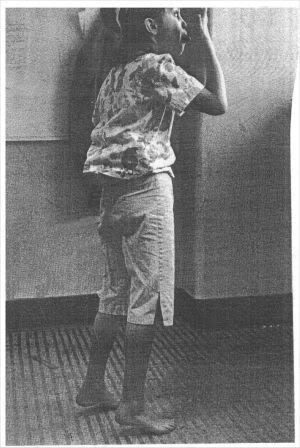

So, the old-school ABA trials? With Lovaas?

This is a kid getting an electric shock:

This is why:

If you were in the wrong place at the wrong time, the wrong age, the wrong functioning level, this could be your life. This what people like them think about people like us.

"Working with" (only possible excuse to spend time with) my friend in special ed was like that. Only I knew on some level functioning level was BS. Because although perceived (on the basis of one or two traits, mind you) functioning level affected how we were treated, the fact was we shared nearly all of the same sensory interests, spoke the same (or at least mutually comprehensible) body language, and even had many of the same difficulties with certain things. And that more than any psych report or anything my mom said taught me that my autism diagnosis meant something real. When you see the first person ever whose body language makes intuitive sense to you, it makes an impression. Even if the other few autistic people you know don't mesh with you as much.

ReplyDeleteAnd that's continued to be the case by the way. I've now met hundreds of autistic people. It's still a minority who make immediate sense to me. But that immediate sense is more than anyone else in the world has ever made to me. (The people who make sense to me, seem to span all diagnostic categories and all supposed functioning labels, and that's a huge part of why I instinctively distrust the things -- they separate people who have a lot in common and group people together who may have next to nothing in common.)

You say there is something to functioning level but there may be less than you think. I often have had an ability to see through mainstream categories, and usually functioning level is decided on the basis of between one and four traits out of possibly hundreds of others. Many "HFA" people can't do daily living tasks and many "LFA" people can. Because functioning level usually has to do with any or all of: perceived IQ, perceived speech ability, perceived amount of stimming, and perceived lack of reaction to people. "Perceived" because each of THOSE can be deceiving. And none of those necessarily say a thing about other abilities or even "how autistic" a person is. (Other people clearly use other categories, I was labeled "low functioning" by professionals at a time when I could speak sometimes and had a high-normal IQ. These days a lot of people still call me that no matter how I reject the categories, because I have lost a few abilities over time, but the ironic thing is that most of the things I can't do now I never could do even when I spoke better and had a higher IQ, like daily living stuff and aspects of language comprehension.)

Anyway I relate to what you describe about meeting other autistic people in the school system. But you may find functioning level means even less than you might expect, even when referring to abilities.

Good post, Amanda. (And good comment, other Amanda!) It explains very well the things I find troubling about how ABA is most often used; I don't have a problem with "dog training"-style methods per se --- like you say, breaking a task down into separate, simple components can be a good way to teach someone a skill, especially if they are having trouble mastering it --- but I *DO* have a big problem with the emphasis on looking normal.

ReplyDelete"Cui bono?" is a good question to ask about a lot of things, and I think it's especially applicable here. It doesn't help Danny --- or any other autistic kid --- to be told over and over again that the way they naturally move, act and speak are Wrong and Bad; it actually probably hurts them by encouraging passivity and learned helplessness. You're trading a child's psychological well-being for a parent's or teacher's not having to be embarrassed or inconvenienced by that child's "weirdness."

thank you for this post.

ReplyDeleteGreat post! I just found your blog through Lindsay's link here.

ReplyDeleteThe only reason they're not about me is that I'm old and verbal enough to not be vulnerable to that kind of abuse. They would be all too happy to practice it on me if they could.

Exactly. When I was young and vulnerable, I wasn't even recognized as autistic, and still got similar treatment (and tons of psych meds). It's all about the perceived weirdness. Very verbal "weirdness", in some cases, as you point out. Functioning labels are a joke.

My first inpatient psych stay at 13 helped me see how ridiculous and divisive a lot of pathologizing labels are, and how much a lot of us have in common underneath them. Interacting with other autistic people (outside my own family!) has kinda confirmed that view.

hi ballastexistenz, I definitely don't think functioning level is a super defined thing. I guess the reason I do think of myself as different from some other ASD people is that I feel I have privilege as a person who passes and doesn't need staff and probably won't need to be on disability when I graduate from college etc. I don't really agree with that thing Sue Rubin wrote about how "hfa people look normal but have special interests, lfa people are just trying hard not to bite themselves and need to be cured"--but at the same time, I think that it would be shitty for me to ignore her reasons for saying something like that, the fact that she needs staff, a device, etc., and also the fact that people make a lot of judgments about her as soon as they see her, which seems to bother her (it would certainly bother me). Those are not my experiences. Also, I don't have to fear getting stuck in an institution because I'm normal-enough-looking and verbal. I feel like it would be shitty for me to act like that's a danger for me, because it's just not, it's claiming a level of oppression that I don't actually experience.

ReplyDeleteI always use cerebral palsy as an analogy for ASD because I think it fits well. There is not a straight line separating "severe" and "mild" cp and listing exactly what the people on each side are able to do. But a person with cp who walks and speaks clearly has a very different experience from someone who uses a device and a wheelchair and needs more help doing things, and they're not in as much danger, either.

Excellent post! I'm glad Lindsay linked to this. The school you described sounds like one majorly f---ed up education program. Sort of a poster child for what is wrong with the way so many ABA programs are marketed and implemented, and underlying that, what is wrong with the *goals* and *values* of so many ABA programs.

ReplyDeleteThis is a beautiful post Amanda. I have always been disstisfied with the standards set by society and the expectatins I am supposed to meet if I want to have any friends. My family was not too fond of me openly discussing my numbering system withmy peers, worried that they will judge me (it is a very long story). They were absolutely right that my peers would think I am "weird," but I was never ashamed of it. I refused to take my mom's advice on how I should behave in school, so that stirred up some conflict. Luckily, my social skills teachers were a little more sympathetic, so they just wanted me to learn to ignore the bullying or find ways to stand up for myself. Eventually, bullies do get tired of teasing, and in my case, they started to give me some respect because I never took anybody's crap. I did at one point seem to inform the whole world of my diagnosis with pride. Not a move I take today, but I feel it did help my past peers understand me better.

ReplyDeleteUnfortunately, many autism and asperger resources are still encouraging normalization. I understand that we should keep good hygiene, not fart in public, and perhaps avoid endless special interest talk with uninterested people. This is more an issue of considertionto others than appearing normal. But our rights to stim, appy our interests passionately, locomote our way, dress comfortably, and such far outweigh other's rights not to feel uncomfortable around us. It is a very easy "offense" for them to get over

Thank you for this. You've summed up my feelings about ABA pretty succinctly. Though I never had any kind of autism therapy (being dxed only a few years ago) I always get a creepy crawly feeling reading about ABA, the way it seems to quash and crush any form of self-expression outside of a very narrow band.

ReplyDeleteI've clicked to follow you, if that's okay. I'm primarily on Dreamwidth/Livejournal, so I don't tend to blog here at all, but I am interested in reading more of your thoughts.

I know I'm a Johnny come lately but I love this post. There's such a narrow view of what is "normal" that it cuts people out and away from living their lives and being free to show their strengths or even just enjoy them quietly, alone. The idea that a child could be spoken to harshly just for nervous fiddling... It's galling, as is the rest and all the worse that happens.

ReplyDeleteYourr the best

ReplyDelete