Dear L,

I need to tell you something. I never completed the staff review form this summer because I was afraid that it would be obvious who I was even if I mailed it in anonymously, and that if I said what I thought, I would not be asked to return to camp. This winter, when I realized that I had not been asked to return anyway, I decided that I would probably write to you and tell you this.

I don't expect you to answer this but I do ask that you read it carefully and think about what I have to say, because I think that camp will be a safer and better place if you read it. I know you're busy with work and preparing for the summer, and that you may not get to it right away. But I have faith that you will read it. Thank you.

As you may or may not know, I was born with a disability. When I was growing up, I never went to a camp like [name of camp] and there were not many social groups for kids with my disability. When I came to camp in 2010, it was the first time that I was able to meet and get to know people with disabilities and this is one of the reasons that camp has been so important to me. Both summers, I told some other counselors that I am disabled and they were supportive, but I generally do not like to tell employers this for fear that they will assume I am not able to perform the functions of a job because of my disability.

In the first session of camp in 2011, a fellow counselor told me that he considered our young campers to be "brats who needed discipline," and that when his campers were annoying him, he wished he could hit them. He was angry with the campers for doing things like becoming upset, crying, being mad at him, or not responding to commands. I tried to defend the campers, but he said that he didn't see why I liked them so much because they were "just brats," and implied that I was bad at my job because I didn't share his views on how to discipline campers. (Through other staff, I later found out that this counselor would do things like bringing food to his cabin that the campers were not allowed to have, and eating it in front of them.)

After having this type of conversation with him a few times, I felt so scared by him that I no longer wanted to be around him. Given the attitudes he expressed toward people with disabilities, I didn't feel safe telling this other counselor that I am disabled. We had become friends during orientation, and he didn't understand that (from my perspective) we could no longer be friends. He expected that I would still want to spend time with him during breaks, but I now tried to avoid him, though I tried not to offend him or make it obvious what I was doing.

I found the situation so upsetting and awkward that I didn't know what to do. I strongly considered quitting camp and leaving immediately. It was hard to stay, but I chose to stay because I cared about my campers and because of the effects on the workload of other staff if I were to suddenly quit. When other staff would have conversations about this counselor, I would participate in them because I was so upset by the situation. I know that this wasn't a good course of action and I'm sorry for talking about another counselor when he wasn't there. It was wrong.

But, when I was able to talk to an authority figure about what happened, I felt like I was in more trouble than the person who had expressed a wish to be violent toward kids with disabilities. I had actually imagined that this counselor might be fired, but my concerns were not even acknowledged, and I did not get the impression that he was ever told his behavior was wrong. Instead, I was told that I shouldn't have "talked about him behind his back," as if it was just an issue of the two of us not getting along. (In fact, we had been friends up to that point. I didn't have a personal problem with him.) I was also told that I should have confronted him directly about why I was upset--but as a person with a disability, I don't feel safe confronting someone who acts so hateful about people with disabilities, and besides, I had already tried to talk to him about it several times.

This was a tough experience that I was really disappointed by, but I got over it and had a great time at camp. I worked hard and dealt with some challenging situations, like being a float in session three and being given responsibility of a very high-need camper in the middle of session four, when D quit. I think that I dealt with these challenges well; even when I was stressed, I never let it affect my positive relationship with my campers. I think this is the most important part of working as support staff, especially with vulnerable populations.

However, I felt like I was seen as a troublemaker after the incident in first session. Several times I was told off for supposedly doing things that I hadn't done, like smoking in camp buildings and disregarding the safety of campers. These things were not true, but the conversations about them always occurred in a public place and were very brief, so I rarely got a chance to explain. I didn't want to arrange a meeting with you to explain why I felt I was being held responsible for things that didn't happen, because it seemed like making a big deal out of nothing. But I knew that you were probably forming a bad impression of me, and I wasn't surprised to learn that I am no longer wanted at camp. I'm incredibly sad to get confirmation, but I am not surprised.

I know I am responsible for what happened because I should have addressed this while it was going on. I can't change it now. But it would mean a lot to me if you would keep my comments in mind when dealing with other staff and campers in future summers.

Thank you so much for reading all of this.

Sincerely,

Amanda

28 December, 2011

26 December, 2011

okay so this is something I wonder about all the time.

whenever I read any mainstream media article about verbal people with autism, the people with autism are so rude! well not necessarily rude, but just really really insensitive to other people's feelings or to being polite.

obviously there are people with and without autism who sometimes make me go, "you're so fucking rude/insensitive!" and I'm sure some people think the same about me, but it's never to the degree portrayed in these articles. like when I'm going to hang out with a friend and I take FOREVER to get ready and delay the whole thing. not nice. or when someone goes, "it's nice to see you, you're not the person I was most looking forward to seeing, but it is nice." (yes I know someone who said this) or even just when you make an effort to do something for someone and they don't say thank you. or when someone doesn't ask how you are doing and only talks about themselves. or interrupts all the time.

stuff happens! people are rude. maybe us more for the sake of argument, but not on the dramatic level portrayed in these newspaper/magazine articles. those articles never look like me or anyone I know and I used to always be like, damn my autism is so fake! all my friends' autism is so fake!

but sometimes I wonder if it just the point of view of the article and I'm wondering if anyone else thinks that might be true. could I make people in my life sound like that if I wanted to?

whenever I read any mainstream media article about verbal people with autism, the people with autism are so rude! well not necessarily rude, but just really really insensitive to other people's feelings or to being polite.

obviously there are people with and without autism who sometimes make me go, "you're so fucking rude/insensitive!" and I'm sure some people think the same about me, but it's never to the degree portrayed in these articles. like when I'm going to hang out with a friend and I take FOREVER to get ready and delay the whole thing. not nice. or when someone goes, "it's nice to see you, you're not the person I was most looking forward to seeing, but it is nice." (yes I know someone who said this) or even just when you make an effort to do something for someone and they don't say thank you. or when someone doesn't ask how you are doing and only talks about themselves. or interrupts all the time.

stuff happens! people are rude. maybe us more for the sake of argument, but not on the dramatic level portrayed in these newspaper/magazine articles. those articles never look like me or anyone I know and I used to always be like, damn my autism is so fake! all my friends' autism is so fake!

but sometimes I wonder if it just the point of view of the article and I'm wondering if anyone else thinks that might be true. could I make people in my life sound like that if I wanted to?

23 December, 2011

the long version

I was a very small boy when I received the bite. My parents tried everything but there is no cure.

Dumbledore said that as long as we took certain precautions, there was no reason I shouldn’t come to school. Once a month I was smuggled out of the castle, into this place, to transform. The tree was placed at the tunnel mouth to stop anyone coming across me while I was dangerous.

I was separated from humans to bite so I bit and scratched myself instead. The villagers heard the noise and the screaming and thought they were hearing particularly violent spirits.

But I sucked it up because that’s what you do, and I was happier than I’d ever been in my life, because I had three friends.

Interestingly when I got older they still didn’t trust me and thought I was a spy.

Probably because it was really cool that I wasn’t human, when they could make jokes about it and use our friendship as an excuse to do something rebellious and exciting. They used to ask me to share my painkillers and my other meds. The tranquilizers were strong because they were made for a werewolf and Sirius especially loved to get out of his mind. It was also cool when they figured out how to use me to scare someone they didn’t like who then hated me for the rest of our lives.

It was pretty cool how I was so intimidated by them, too, since I’d never had friends before and everything.

This didn’t mean that I could be trusted to protect their family. I’m a fucking werewolf, guys. Clearly I eat faces.

Awesome.

Dumbledore said that as long as we took certain precautions, there was no reason I shouldn’t come to school. Once a month I was smuggled out of the castle, into this place, to transform. The tree was placed at the tunnel mouth to stop anyone coming across me while I was dangerous.

I was separated from humans to bite so I bit and scratched myself instead. The villagers heard the noise and the screaming and thought they were hearing particularly violent spirits.

But I sucked it up because that’s what you do, and I was happier than I’d ever been in my life, because I had three friends.

Interestingly when I got older they still didn’t trust me and thought I was a spy.

Probably because it was really cool that I wasn’t human, when they could make jokes about it and use our friendship as an excuse to do something rebellious and exciting. They used to ask me to share my painkillers and my other meds. The tranquilizers were strong because they were made for a werewolf and Sirius especially loved to get out of his mind. It was also cool when they figured out how to use me to scare someone they didn’t like who then hated me for the rest of our lives.

It was pretty cool how I was so intimidated by them, too, since I’d never had friends before and everything.

This didn’t mean that I could be trusted to protect their family. I’m a fucking werewolf, guys. Clearly I eat faces.

Awesome.

18 December, 2011

Also I know this seems self-indulgent and more suited for tumblr but a while ago I took the Meyers-Briggs personality test and I did not get one of the stereotypical autism results. (I think it's INTJ? I got ISFJ.) It might just be one of those things where you interpret the results to fit you, like with horoscopes, but the description of my type seemed to fit me really well.

I'm not sure why, but I found that really comforting. I think if you have a mental disability you get used to hearing yourself described in a way that doesn't fit you at all. Well, at least I do. It's been really cool to realize that I can identify as having autism without having to try to change my personality or values to fit a stereotype of what that is supposed to be. I feel like I've only recently come around to be able to do that.

I'm not sure why, but I found that really comforting. I think if you have a mental disability you get used to hearing yourself described in a way that doesn't fit you at all. Well, at least I do. It's been really cool to realize that I can identify as having autism without having to try to change my personality or values to fit a stereotype of what that is supposed to be. I feel like I've only recently come around to be able to do that.

pink-collar jobs and autism

I take it really hard when I see someone defending the ability of A/autistic people to work or more generally "contribute to society" (not an idea I'm fond of) by saying things like:

*we can hyperfocus on something and do it really well.

*we might seem rude but if we work in a geeky environment, like if we are video game programmers, this won't matter! And if we don't our coworkers can learn to understand and forgive our rudeness because we do a good job.

*we may have more needs in some areas but we have fewer needs in other areas because we don't party/spend time on Facebook/care about fashion/play sports/something else stereotypically non-autistic. (It's too bad because the blog where I read this had a good point about "special needs" not always meaning "more needs" but I thought it wasn't helpful to rely on stereotypes this way.)

*we might have special interests in science or art that lead to us being amazingly skilled in those areas./We might have "splinter skills" or "savant skills."

People with and without autism say these things and they mean well. But I don't like it, not just because I am offended by stereotypes or something, but because it is personally threatening to me.

Every job I've ever held, and probably every job I've ever even applied for or been interested in, has been a pink-collar job.

I feel a little weird using the term pink-collar because it was coined for kind of a critical use--it refers to jobs usually done by women and the reason these jobs are in their own category is because they tend to be lower-paid than traditionally masculine jobs that have the same workload and educational requirements. But pink-collar is the only term I can find that easily covers the sort of jobs I am thinking of.

Some examples of pink-collar jobs are hairdressing, nursing, teaching, and waitressing. These jobs are a bit different from the kinds of jobs people are usually thinking of when they talk about how Autistic people can succeed in the workplace, because a lot of the job is about interacting with people other than coworkers. These don't all apply for every pink-collar job, but some of the requirements for a pink-collar job might be:

*treating people courteously and being friendly

*not hurting or abusing people

*being well-suited to working with kids

*remaining polite when someone gets mad at you

*being able to put someone else's well-being ahead of your own

*doing everything you can to fulfill someone's request

It is probably apparent that none of these qualities are stereotypically Autistic. I even see comments to that effect thrown around without much thought--that people with autism aren't good at customer service, or that we don't like kids. I'm not just trying to be all, "I'm good at customer service and I like kids, your argument is invalid!" but to point out that when even "positive" descriptions of Autistic people's work imply that we can't do certain kinds of work, it makes it harder for us to get jobs, or be open about our disability if we do get those jobs.

I know I'm not a super rare exception in a world of Autistic people who want to be electrical engineers, because I know lots of Autistic people, especially women, who want to work in special education. Special ed is a really good example of a field where, if you were applying for a job, you would want to convince your potential employer that you had all the qualities on that list. Which is to say that if your employer has been fed stereotypes of what Autistic people are like and what kind of work we can do, telling them you have autism could really hurt your chances of getting the job.

I know some people who will be open about their autism when applying for a job. I would never, ever do this. Right now I am looking for a job in healthcare and it scares me a lot to know that my disability label is associated with being violent, rude, and uncaring. I really love having this blog because I always wanted to write something that people liked and got something out of, but I regularly consider deleting it because it would be so easy for anyone who googles me to find out I have autism.

Basically what I'm trying to say is that even though my disability doesn't make me better at doing pink-collar jobs, I don't think it makes me worse at them, and I would like my suitability for them to be judged by who I am as a person instead of my disability label. I feel that even when people try to talk positively about what Autistic people can do in the workplace, they often ignore the fact that some Autistic people don't want to work in an office or in a stereotypically un-social field like science. So they don't defend us against some of the stereotypes about what we can and can't do, and sometimes they even reinforce those stereotypes by implying we are best at certain kinds of work.

I'd also like to point out that while my family was able to pay for me to attend college and I was (barely) able to finish my degree, a lot of people with autism don't have the option of the white-collar jobs we're supposed to be so good at. If you spend all your breath arguing that we can be engineers or architects, that doesn't help people who don't have the money or don't have the ability to get the education to do those kinds of jobs.

(NB that this post might not be relevant to people with autism who can't work, and some of it might be relevant to people with other disabilities like mood and psychotic disorders and intellectual disabilities.)

*we can hyperfocus on something and do it really well.

*we might seem rude but if we work in a geeky environment, like if we are video game programmers, this won't matter! And if we don't our coworkers can learn to understand and forgive our rudeness because we do a good job.

*we may have more needs in some areas but we have fewer needs in other areas because we don't party/spend time on Facebook/care about fashion/play sports/something else stereotypically non-autistic. (It's too bad because the blog where I read this had a good point about "special needs" not always meaning "more needs" but I thought it wasn't helpful to rely on stereotypes this way.)

*we might have special interests in science or art that lead to us being amazingly skilled in those areas./We might have "splinter skills" or "savant skills."

People with and without autism say these things and they mean well. But I don't like it, not just because I am offended by stereotypes or something, but because it is personally threatening to me.

Every job I've ever held, and probably every job I've ever even applied for or been interested in, has been a pink-collar job.

I feel a little weird using the term pink-collar because it was coined for kind of a critical use--it refers to jobs usually done by women and the reason these jobs are in their own category is because they tend to be lower-paid than traditionally masculine jobs that have the same workload and educational requirements. But pink-collar is the only term I can find that easily covers the sort of jobs I am thinking of.

Some examples of pink-collar jobs are hairdressing, nursing, teaching, and waitressing. These jobs are a bit different from the kinds of jobs people are usually thinking of when they talk about how Autistic people can succeed in the workplace, because a lot of the job is about interacting with people other than coworkers. These don't all apply for every pink-collar job, but some of the requirements for a pink-collar job might be:

*treating people courteously and being friendly

*not hurting or abusing people

*being well-suited to working with kids

*remaining polite when someone gets mad at you

*being able to put someone else's well-being ahead of your own

*doing everything you can to fulfill someone's request

It is probably apparent that none of these qualities are stereotypically Autistic. I even see comments to that effect thrown around without much thought--that people with autism aren't good at customer service, or that we don't like kids. I'm not just trying to be all, "I'm good at customer service and I like kids, your argument is invalid!" but to point out that when even "positive" descriptions of Autistic people's work imply that we can't do certain kinds of work, it makes it harder for us to get jobs, or be open about our disability if we do get those jobs.

I know I'm not a super rare exception in a world of Autistic people who want to be electrical engineers, because I know lots of Autistic people, especially women, who want to work in special education. Special ed is a really good example of a field where, if you were applying for a job, you would want to convince your potential employer that you had all the qualities on that list. Which is to say that if your employer has been fed stereotypes of what Autistic people are like and what kind of work we can do, telling them you have autism could really hurt your chances of getting the job.

I know some people who will be open about their autism when applying for a job. I would never, ever do this. Right now I am looking for a job in healthcare and it scares me a lot to know that my disability label is associated with being violent, rude, and uncaring. I really love having this blog because I always wanted to write something that people liked and got something out of, but I regularly consider deleting it because it would be so easy for anyone who googles me to find out I have autism.

Basically what I'm trying to say is that even though my disability doesn't make me better at doing pink-collar jobs, I don't think it makes me worse at them, and I would like my suitability for them to be judged by who I am as a person instead of my disability label. I feel that even when people try to talk positively about what Autistic people can do in the workplace, they often ignore the fact that some Autistic people don't want to work in an office or in a stereotypically un-social field like science. So they don't defend us against some of the stereotypes about what we can and can't do, and sometimes they even reinforce those stereotypes by implying we are best at certain kinds of work.

I'd also like to point out that while my family was able to pay for me to attend college and I was (barely) able to finish my degree, a lot of people with autism don't have the option of the white-collar jobs we're supposed to be so good at. If you spend all your breath arguing that we can be engineers or architects, that doesn't help people who don't have the money or don't have the ability to get the education to do those kinds of jobs.

(NB that this post might not be relevant to people with autism who can't work, and some of it might be relevant to people with other disabilities like mood and psychotic disorders and intellectual disabilities.)

Labels:

asd,

autism pop culture,

class,

gender,

pink-collar,

work

16 December, 2011

I am working on a post about how much I hate this (not this particular post, but the whole discussion), but I got sidetracked by thinking about a particular intersection of sexism and ableism.

I don't think I'm the only person to have witnessed this series of events:

A young woman in a staff role encounters a developmentally disabled guy who "accidentally" touches her breasts, jokes about her being a stripper, jerks off in front of her, etc.

The woman is upset. She talks to a more experienced staff person, or to her supervisor, and is politely told to get over it.

Don't be upset, it's funny. He can't hurt you.

Don't be mad at him, feel sorry for him because he doesn't know any better.

When I talk about this I don't mean to imply that men with developmental disabilities sexually harass women more than other men. I'm also not sure that people's reactions are that different when it comes down to it. The staff/disabled power dynamic is just stacked on top of the idea that men should probably get to do whatever they want, so that both people are getting a shitty consolation prize for not having power.

I mean, what you tell a woman in this situation basically boils down to, "Why not be a good sport and let him have this one thing? At least you're not disabled."

I don't think I'm the only person to have witnessed this series of events:

A young woman in a staff role encounters a developmentally disabled guy who "accidentally" touches her breasts, jokes about her being a stripper, jerks off in front of her, etc.

The woman is upset. She talks to a more experienced staff person, or to her supervisor, and is politely told to get over it.

Don't be upset, it's funny. He can't hurt you.

Don't be mad at him, feel sorry for him because he doesn't know any better.

When I talk about this I don't mean to imply that men with developmental disabilities sexually harass women more than other men. I'm also not sure that people's reactions are that different when it comes down to it. The staff/disabled power dynamic is just stacked on top of the idea that men should probably get to do whatever they want, so that both people are getting a shitty consolation prize for not having power.

I mean, what you tell a woman in this situation basically boils down to, "Why not be a good sport and let him have this one thing? At least you're not disabled."

Labels:

gender,

quote unquote mental age,

sexism,

staff infection

11 December, 2011

Elephant

I had a dream I went to Hogwarts except instead of being for magic it was for disabled people. All my RL and Internet disabled friends were there and I felt anxious about who to hang out with.

We were each supposed to put on a little skit about our experience with our disability. I forgot to prepare my skit but I did at the last minute. My friend Gabe (who isn't disabled, but this wasn't a very well-constructed dream) was in the skit.

In my skit I am an elephant wearing a trunk made out of blue construction paper. Gabe tells me it's awful for me to have a trunk, so the next time I see him I'm hiding the trunk under a huge coat.

"Why are you hiding your face under that coat? What's wrong with you?"

"I'm an elephant."

"Don't be stupid! You're not an elephant. You don't have a trunk."

I take my trunk out from under my coat. Gabe stares at me.

"What the fuck is wrong with your face?"

I timidly stumble offstage. Everyone likes my skit.

We were each supposed to put on a little skit about our experience with our disability. I forgot to prepare my skit but I did at the last minute. My friend Gabe (who isn't disabled, but this wasn't a very well-constructed dream) was in the skit.

In my skit I am an elephant wearing a trunk made out of blue construction paper. Gabe tells me it's awful for me to have a trunk, so the next time I see him I'm hiding the trunk under a huge coat.

"Why are you hiding your face under that coat? What's wrong with you?"

"I'm an elephant."

"Don't be stupid! You're not an elephant. You don't have a trunk."

I take my trunk out from under my coat. Gabe stares at me.

"What the fuck is wrong with your face?"

I timidly stumble offstage. Everyone likes my skit.

09 December, 2011

discretion

I think this is my #1 song right now, Clayton very sweetly tried to get David Bazan to play it when we saw him on my birthday but I guess he doesn't play it with his current band. Feeling weird about blogging but probably won't make any real decisions until I become employed (this is probably not the best time in American history to set "when I become employed" as a prerequisite for doing something, but oh well).

having no idea that his youngest son was dead

the farmer and his sweet young wife slept soundly in his bed

in the shadow of the mountain as the cattle hung their heads

grazing only feet from where the broken body lay

and would lay undiscovered for another several days

when the farmer would find vultures at their banquet in the hay

the killer traveled eastward in a golden brown sedan

weighing his most recent deviation from the plan

counting down the hours till the sun came up again

hired to hit the farmer by the farmer's asshole son

had not yet decided between poison or a gun

suddenly he realized he would not use either one

having no idea that his youngest son was dead

the farmer and his sweet young wife slept soundly in his bed

in the shadow of the mountain as the cattle hung their heads

grazing only feet from where the broken body lay

and would lay undiscovered for another several days

when the farmer would find vultures at their banquet in the hay

the killer traveled eastward in a golden brown sedan

weighing his most recent deviation from the plan

counting down the hours till the sun came up again

hired to hit the farmer by the farmer's asshole son

had not yet decided between poison or a gun

suddenly he realized he would not use either one

06 December, 2011

You're (Still) Going To Die In There: boring uses of clueless sensitivity

“If you like the jar with the baby’s leg, wait until you see the jar holding the baby’s head. If one actress with Down syndrome doesn’t provide enough Tod Browning-style otherness for you, don’t worry — there are two. If the line about snorting cocaine off a high school girl’s nipples doesn’t do it for you, maybe the scene of the sobbing naked man masturbating will.”

—New York Times American Horror Story review

One of these things is not like the others!

It’s perfectly reasonable for critics to take issue with portrayals of disabled characters that use them as a genre trope or try to shock the audience with the disabled character’s appearance. Lots of horror movies and TV shows do this.

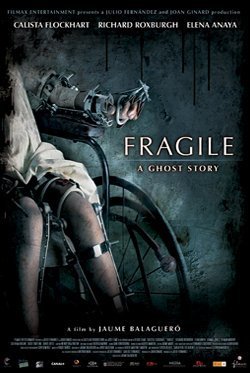

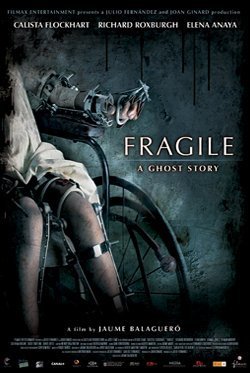

(While we’re on the subject can I just show you my favorite horror DVD cover of all time:

LOLOL. Terrifying.)

However, I really wish critics, in their rush to be sensitive about disability issues, would actually take a step back and look at what they’re saying. Which in this case, seems to boil down to the idea that a person with Down Syndrome is the same as a jar with part of a dead baby in it. And that an actor with a disability that affects their appearance would only be cast in a TV show or movie as a circus freak.

To be fair, I don’t really think this critic would be against an actor with Down Syndrome appearing in some kind of inspirational/depressing movie about the family of someone with a disability. I don’t think they would consider that a “freakish” performance. But in addition to the fact that you shouldn’t assume all disabled characters in the horror genre are functioning as freaks, I’m also not sure why critics are quick to jump all over the “insensitivity” of characters like Addie in AHS, when they don’t seem especially plugged in to notice what is wrong about more “tasteful” portrayals of disability—which in my opinion can be equally offensive.

I definitely don’t speak for all disabled people when I say this, but I prefer horror tropes of disability to tasteful tropes. Disabled horror characters have style—rusty, terrifying wheelchairs and braces more suited for steampunk conventions than actually helping someone get around. Their unsteady gait isn’t depressing, it stops you in your tracks with fear. If they’re bad, they kill people, and if they’re good, they can help you with their psychic powers. They’re not people to underestimate.

Of course they’re usually shitty characters, but as shitty characters go, I love them a lot. And because their very nature means they are not “tasteful,” they often become more human and likable than the disabled characters in a straight-faced portrayal of disability.

I wish that critics would wait to talk about disability until they’re ready to actually care about it and engage with it genuinely. The more I see people complain about Addie on AHS—in exactly the same way, and for some reason never mentioning other disabled characters on the show, like she’s the agreed-upon thing that’s offensive—the more it looks like they’re doing it to earn some kind of merit badge. “I’m sensitive to portrayals of disability in pop culture!” No, you’re not. Because if you were, you would care about things like whether disabled characters are unique, have realistic problems, are charismatic, are POV characters, and don’t tragically die at the end of the movie. Your primary focus wouldn’t be whether you can lazily compare Jamie Brewer to the actors in Freaks—which happens to be a great movie despite not being “tasteful” in the slightest.

As long as so few disabled characters are good, it’s really hard for them to be notably bad, and there’s something so clueless about condemning Addie Langdon when there are so many worse characters running around in this and other genres. In the end it doesn’t matter if the Burned-Face Man chokes you with a pillow in the attic, or a Lifetime mom ends your suffering in a more wholesome way—you’re going to die in there.

—New York Times American Horror Story review

One of these things is not like the others!

It’s perfectly reasonable for critics to take issue with portrayals of disabled characters that use them as a genre trope or try to shock the audience with the disabled character’s appearance. Lots of horror movies and TV shows do this.

(While we’re on the subject can I just show you my favorite horror DVD cover of all time:

LOLOL. Terrifying.)

However, I really wish critics, in their rush to be sensitive about disability issues, would actually take a step back and look at what they’re saying. Which in this case, seems to boil down to the idea that a person with Down Syndrome is the same as a jar with part of a dead baby in it. And that an actor with a disability that affects their appearance would only be cast in a TV show or movie as a circus freak.

To be fair, I don’t really think this critic would be against an actor with Down Syndrome appearing in some kind of inspirational/depressing movie about the family of someone with a disability. I don’t think they would consider that a “freakish” performance. But in addition to the fact that you shouldn’t assume all disabled characters in the horror genre are functioning as freaks, I’m also not sure why critics are quick to jump all over the “insensitivity” of characters like Addie in AHS, when they don’t seem especially plugged in to notice what is wrong about more “tasteful” portrayals of disability—which in my opinion can be equally offensive.

I definitely don’t speak for all disabled people when I say this, but I prefer horror tropes of disability to tasteful tropes. Disabled horror characters have style—rusty, terrifying wheelchairs and braces more suited for steampunk conventions than actually helping someone get around. Their unsteady gait isn’t depressing, it stops you in your tracks with fear. If they’re bad, they kill people, and if they’re good, they can help you with their psychic powers. They’re not people to underestimate.

Of course they’re usually shitty characters, but as shitty characters go, I love them a lot. And because their very nature means they are not “tasteful,” they often become more human and likable than the disabled characters in a straight-faced portrayal of disability.

I wish that critics would wait to talk about disability until they’re ready to actually care about it and engage with it genuinely. The more I see people complain about Addie on AHS—in exactly the same way, and for some reason never mentioning other disabled characters on the show, like she’s the agreed-upon thing that’s offensive—the more it looks like they’re doing it to earn some kind of merit badge. “I’m sensitive to portrayals of disability in pop culture!” No, you’re not. Because if you were, you would care about things like whether disabled characters are unique, have realistic problems, are charismatic, are POV characters, and don’t tragically die at the end of the movie. Your primary focus wouldn’t be whether you can lazily compare Jamie Brewer to the actors in Freaks—which happens to be a great movie despite not being “tasteful” in the slightest.

As long as so few disabled characters are good, it’s really hard for them to be notably bad, and there’s something so clueless about condemning Addie Langdon when there are so many worse characters running around in this and other genres. In the end it doesn’t matter if the Burned-Face Man chokes you with a pillow in the attic, or a Lifetime mom ends your suffering in a more wholesome way—you’re going to die in there.

Labels:

american horror story,

disability as metaphor,

down syndrome,

freaks,

genre,

tv

05 December, 2011

important lifestyle change!

I've decided to stop trying to have an even skin tone

just like I don't have to pretend to be a genius because I have bad brains, I also don't have to go over my face with a fine-toothed metaphorical comb, especially because I have rosacea, and hiding that will take my entire life.

if you have the kind of stunned/stumbling mind that I have, having to have an even skin tone before you are officially "dressed" means that getting dressed never happens and you float around in pajamas for really long periods of time. people need to be dressed. at least I do. it does take a long time and sometimes it's like, "because of the amount of time it took to get dressed, I'm not going to do anything today anyway." but my lifestyle change is totally chopping some minutes off the getting dressed torture!

I'd also like to point out as an aside how horrible it is when you do spend your entire life putting on makeup and then later in the day it starts to look kind of like a mask, this is awful, it makes me feel awful, I am 23.

new lifestyle:

cover up anything on my face that looks like the exit wound from a bullet

lipstick/lipgloss

now ready to put on clothes

just like I don't have to pretend to be a genius because I have bad brains, I also don't have to go over my face with a fine-toothed metaphorical comb, especially because I have rosacea, and hiding that will take my entire life.

if you have the kind of stunned/stumbling mind that I have, having to have an even skin tone before you are officially "dressed" means that getting dressed never happens and you float around in pajamas for really long periods of time. people need to be dressed. at least I do. it does take a long time and sometimes it's like, "because of the amount of time it took to get dressed, I'm not going to do anything today anyway." but my lifestyle change is totally chopping some minutes off the getting dressed torture!

I'd also like to point out as an aside how horrible it is when you do spend your entire life putting on makeup and then later in the day it starts to look kind of like a mask, this is awful, it makes me feel awful, I am 23.

new lifestyle:

cover up anything on my face that looks like the exit wound from a bullet

lipstick/lipgloss

now ready to put on clothes

note to myself for future annoying pop culture posts

tv shows I've adopted this fall and my feelings about disability on those shows:

the vampire diaries (n/a, just as tvd is n/a for anything that relates to minorities in any way, except for the hilarious black witches thing which is as bizarre as it is partly because of the show's refusal to acknowledge that anything bad ever happened to black people in America)

china, il (n/a it's brad neely)

my little pony friendship is magic (really great)

the fades (good--not a big thing but they cast actors with disabilities)

bedlam (worst thing EVER, as I explained here)

game of thrones (awesome)

american horror story (awesome, this might take some explaining, but I'm sticking to my guns)

(I also finished united states of tara and six feet under, both of which I can imagine having things to say about, but I've been watching both shows for so long I don't think I ever will)

the vampire diaries (n/a, just as tvd is n/a for anything that relates to minorities in any way, except for the hilarious black witches thing which is as bizarre as it is partly because of the show's refusal to acknowledge that anything bad ever happened to black people in America)

china, il (n/a it's brad neely)

my little pony friendship is magic (really great)

the fades (good--not a big thing but they cast actors with disabilities)

bedlam (worst thing EVER, as I explained here)

game of thrones (awesome)

american horror story (awesome, this might take some explaining, but I'm sticking to my guns)

(I also finished united states of tara and six feet under, both of which I can imagine having things to say about, but I've been watching both shows for so long I don't think I ever will)

03 December, 2011

Hercules

sorry for spamming you guys with this, but I figured it would be entertaining to at least one person. I kind of think both these papers are bullshit--I mean they were pass/fail and I had a lot of stuff going on so I wrote about themes that are easy for me to find in anything. But I do think the fact that these themes are so easy to find indicates a lot about how deep in the values are.

HERCULES--ABILITY

Supernatural conditions are sometimes portrayed as being analogous to disabilities; for example, telepathy in True Blood or lycanthropy in the Harry Potter books. It’s not necessary that the analogously “disabled” character lack an ability that other people have, as long as he or she has the wrong abilities compared to other people. Hercules is easily interpreted as part of the magic-as-disability tradition, as his super strength impairs his ability to live normally and fit in with his community.

Hercules can sometimes use his super strength to do chores for his adoptive parents but, perhaps because he lives in a world set up for humans with an ordinary level of strength, he often expends too much strength and ends up breaking buildings and injuring people, which causes him to be unpopular in his community, which labels him a “freak.” Although his adoptive parents love Hercules, they come to accept that he doesn’t fit in their community and must journey elsewhere to be successful.

Hercules’s journey can be seen as a positive message for viewers with disabilities or other people who don’t match the standards of their community. As he moves into different environments and roles--training with Phil, performing heroic deeds in Thebes, partying on Mount Olympus as a god among gods--we see that Hercules, who was not good at anything in his parents’ town, can be good at everything when different things are expected of him. However, his clumsiness isn’t completely cured when he becomes a hero, and this is realistic. He also chooses an imperfect existence as a human over existence as a god, where he presumably wouldn’t have to deal with the issue of clumsiness--showing that if he has a life he’s proud of and happy with, he doesn’t mind not being good at everything.

Like many magic-as-disability works of fiction, Hercules fails to deliver a completely positive message about disability because the resolution of the “disabled” character’s problems is less than applicable to real life. Ultimately, a character with super strength can’t be a real disabled character for two reasons. First, super strength doesn’t resemble any real-life disability so it’s not as easy to identify Hercules as disabled, which limits his ability to be a role model for disabled kids or bring images of disabled people into the minds of non-disabled kids. (This isn’t necessarily the case for all “magical” disabilities; a magical illness, for example, can be easily read as resembling a real illness.) Second, Hercules finds a solution for his problems that’s nearly perfect, and steps into a new life where he’s universally admired. While it is important to show that someone who’s labelled a loser or a freak can be successful by different standards, Hercules’s tremendous success is somewhat problematic because it sets a standard viewers, not having superpowers, may not be able to aspire to or identify with.

Notably, the magic-as-disability aspects of the character are not at all present in the original myth. In the myth, Hercules/Heracles’s problems come from a fact that is completely excised from the movie; Hera, his father’s wife, is not his mother, and even though he lives with his mother and stepfather instead of on Olympus, Hera nonetheless hates him and causes him various problems. Although evil stepmothers are certainly acceptable in Disney movies, the portrayal of infidelity that would be required by an accurate adaptation of the myth would probably be considered inappropriate for a children’s movie. Therefore, the villain of Hercules’s story becomes Hades, who is not evil in classical mythology; and Hercules’s main motivation comes from within.

Protagonists who are unpopular, or who are initially perceived as “losers,” can be appealing in American movies, but don’t really fit with classical values, which had less of a focus on the individual. In the Disney movie, Hercules doesn’t want to be a hero for the sake of glory or other more classical values, but for more modern reasons, and ones that position him as a minority or an outcast in his community, in the same way as other Disney characters like Belle and Mulan.

HERCULES--ABILITY

Supernatural conditions are sometimes portrayed as being analogous to disabilities; for example, telepathy in True Blood or lycanthropy in the Harry Potter books. It’s not necessary that the analogously “disabled” character lack an ability that other people have, as long as he or she has the wrong abilities compared to other people. Hercules is easily interpreted as part of the magic-as-disability tradition, as his super strength impairs his ability to live normally and fit in with his community.

Hercules can sometimes use his super strength to do chores for his adoptive parents but, perhaps because he lives in a world set up for humans with an ordinary level of strength, he often expends too much strength and ends up breaking buildings and injuring people, which causes him to be unpopular in his community, which labels him a “freak.” Although his adoptive parents love Hercules, they come to accept that he doesn’t fit in their community and must journey elsewhere to be successful.

Hercules’s journey can be seen as a positive message for viewers with disabilities or other people who don’t match the standards of their community. As he moves into different environments and roles--training with Phil, performing heroic deeds in Thebes, partying on Mount Olympus as a god among gods--we see that Hercules, who was not good at anything in his parents’ town, can be good at everything when different things are expected of him. However, his clumsiness isn’t completely cured when he becomes a hero, and this is realistic. He also chooses an imperfect existence as a human over existence as a god, where he presumably wouldn’t have to deal with the issue of clumsiness--showing that if he has a life he’s proud of and happy with, he doesn’t mind not being good at everything.

Like many magic-as-disability works of fiction, Hercules fails to deliver a completely positive message about disability because the resolution of the “disabled” character’s problems is less than applicable to real life. Ultimately, a character with super strength can’t be a real disabled character for two reasons. First, super strength doesn’t resemble any real-life disability so it’s not as easy to identify Hercules as disabled, which limits his ability to be a role model for disabled kids or bring images of disabled people into the minds of non-disabled kids. (This isn’t necessarily the case for all “magical” disabilities; a magical illness, for example, can be easily read as resembling a real illness.) Second, Hercules finds a solution for his problems that’s nearly perfect, and steps into a new life where he’s universally admired. While it is important to show that someone who’s labelled a loser or a freak can be successful by different standards, Hercules’s tremendous success is somewhat problematic because it sets a standard viewers, not having superpowers, may not be able to aspire to or identify with.

Notably, the magic-as-disability aspects of the character are not at all present in the original myth. In the myth, Hercules/Heracles’s problems come from a fact that is completely excised from the movie; Hera, his father’s wife, is not his mother, and even though he lives with his mother and stepfather instead of on Olympus, Hera nonetheless hates him and causes him various problems. Although evil stepmothers are certainly acceptable in Disney movies, the portrayal of infidelity that would be required by an accurate adaptation of the myth would probably be considered inappropriate for a children’s movie. Therefore, the villain of Hercules’s story becomes Hades, who is not evil in classical mythology; and Hercules’s main motivation comes from within.

Protagonists who are unpopular, or who are initially perceived as “losers,” can be appealing in American movies, but don’t really fit with classical values, which had less of a focus on the individual. In the Disney movie, Hercules doesn’t want to be a hero for the sake of glory or other more classical values, but for more modern reasons, and ones that position him as a minority or an outcast in his community, in the same way as other Disney characters like Belle and Mulan.

cure in Disney movies

I wrote this paper for an exco I took last term and I just found it when Mtthw inexplicably asked for me to repost the notes I took for the class. It is too long for tumblr, so have fun.

DISABILITY AND NORMALCY IN SLEEPING BEAUTY AND THE LITTLE MERMAID

There is often conflict between the disabled community and mainstream society about what is best for disabled people. Often, disabled people think that success involves putting someone in a situation where they can be as happy and functional as possible; while mainstream society thinks that success means altering someone until they appear “normal.” While actual disabled characters don’t usually appear in Disney movies (except for villains like Captain Hook), these kind of values can be read in the treatment of non-human characters who are different from humans or lack abilities that humans have.

An example of a non-human character who sends a positive message about disability is Tinkerbell in Peter Pan. She can’t talk, but this is never a problem, because everyone in Tinkerbell’s life has learned to understand the way she communicates. Even though she wasn’t created to make this point, Tinkerbell can nonetheless make the point to viewers that she doesn’t need to be altered to fit in with the other characters.

Some non-human characters who do alter themselves and attempt to be human are the three good fairies in Sleeping Beauty and Ariel in The Little Mermaid; and each character shows the problems inherent in attempting to be “normal” rather than aiming to be successful as yourself. Each of these characters is competent when she’s in her natural form and environment, but when expected to perform as humans, they are all lacking.

In their non-human form, the fairies are not as powerful as Maleficent, but they are the most powerful characters in the movie aside from her and it is almost solely through their actions that Aurora is saved from the curse. When they are human, they make one of the big mistakes of the narrative that allows Maleficent to find out where Aurora is. The mistake they make is not just because they are human, but precisely because they are fairies trying to be human who have realized they can’t pretend to be human any longer.

As humans, the fairies are portrayed as lacking either the cognitive abilities or the experience (if not both) to perform tasks like cooking, cleaning, and making clothes. In real life, a person who couldn’t cook or clean for herself wouldn’t be able to live without help, and adults who can’t live without help are often treated rather harshly; but in the case of the fairies, their inability to do these things doesn’t mean they’re seen as defective, but simply that they’re trying to be something they aren’t. Their lapse into using magic again, while it happens at an inconvenient time, is the natural result of putting themselves in an unnatural situation.

Therefore, Sleeping Beauty has a positive portrayal of its “disabled” characters. Their inability to perform normal tasks is humorous, and ultimately not a problem for them, because it is acceptable for them to live differently and rely on other skills to take care of themselves. Humanity is not a goal, but simply something they tried and failed, and then abandoned without seeing their failure as reflecting badly on them.

In The Little Mermaid, however, Ariel’s desire to be a human is a goal that, from the perspective of the movie, she has to achieve at all costs. It wouldn’t really be accurate to say that she desires Eric above all, because she is interested in humans from the beginning and seems to fall in love with him because he’s the first human she sees. While the fairies’ disguise as peasants doesn’t seem like something most viewers could relate to, Ariel’s longing for humanity is more comparable to the way real disabled people are expected to long for normalcy; it’s not just another way of being, it’s an inherently better life.

Objectively, Ariel’s life isn’t bad, but she sees it as inferior: “Flipping your fins you don’t get too far/Legs are required for jumping, dancing,” she sings, ignoring the speed and grace of her own movement. There’s nothing strange about a sheltered teenager being interested in people from another place, but it does become disturbing how Ariel dismisses her own body as nothing but an obstacle to human life, and that this is portrayed as not mere teenage restlessness, but a sensible outlook.

Ariel’s initial life as a human is also comparable to the life of a disabled person trying to be as normal as possible. In real life, a disabled person trying to function as a non-disabled person has to make sacrifices non-disabled people don’t have to make. As a human Ariel can no longer do what she did best as a mermaid (singing), and, most importantly, cannot communicate. (It’s interesting that her inability to communicate keeps Ariel from even being able to tell people that she used to be a mermaid. As is often expected to happen when disabled people are “cured,” she completely drops the identity she had before.)

The Little Mermaid had the potential to be a more unique story about a nonstandard character trying to be normal. In addition to losing her voice, the mermaid in the original story finds it incredibly painful to walk and dance, but does so anyway in order to be attractive to the prince; and she ultimately isn’t able to land the prince, partly because she has given up her ability to communicate so he doesn’t know that she’s the person who saved him. In the fairy tale, the mermaid’s attempt to be human is tragic.

Obviously, the Disney version of the story could not be tragic because that’s not how Disney movies are. But the story could have been given a happy ending in which Ariel went back to being a mermaid without losing her relationship or her zest for life. Instead, the Disney movie glosses over Ariel’s sacrifice, by making her only lose her voice instead of also being in pain; and in the end, she is magically cured of both her lack of humanity and the difficulties that a magical creature trying to be human would have (her voicelessness).

The Little Mermaid has often been identified as a problematic movie in terms of gender, because Ariel changes her body for a man. But it’s also problematic in terms of disability, because Ariel must change herself to a more normal form to realize her dreams. While in Sleeping Beauty, the fairies’ attempt to be human is an impetuous bad idea, it’s presented as the only way Ariel can be happy. Viewers are told not only a)having a normal body is worth the sacrifices, but b)don’t worry about that, because actually, switching from abnormal to normal will become easy and eventually have no drawbacks attached at all.

DISABILITY AND NORMALCY IN SLEEPING BEAUTY AND THE LITTLE MERMAID

There is often conflict between the disabled community and mainstream society about what is best for disabled people. Often, disabled people think that success involves putting someone in a situation where they can be as happy and functional as possible; while mainstream society thinks that success means altering someone until they appear “normal.” While actual disabled characters don’t usually appear in Disney movies (except for villains like Captain Hook), these kind of values can be read in the treatment of non-human characters who are different from humans or lack abilities that humans have.

An example of a non-human character who sends a positive message about disability is Tinkerbell in Peter Pan. She can’t talk, but this is never a problem, because everyone in Tinkerbell’s life has learned to understand the way she communicates. Even though she wasn’t created to make this point, Tinkerbell can nonetheless make the point to viewers that she doesn’t need to be altered to fit in with the other characters.

Some non-human characters who do alter themselves and attempt to be human are the three good fairies in Sleeping Beauty and Ariel in The Little Mermaid; and each character shows the problems inherent in attempting to be “normal” rather than aiming to be successful as yourself. Each of these characters is competent when she’s in her natural form and environment, but when expected to perform as humans, they are all lacking.

In their non-human form, the fairies are not as powerful as Maleficent, but they are the most powerful characters in the movie aside from her and it is almost solely through their actions that Aurora is saved from the curse. When they are human, they make one of the big mistakes of the narrative that allows Maleficent to find out where Aurora is. The mistake they make is not just because they are human, but precisely because they are fairies trying to be human who have realized they can’t pretend to be human any longer.

As humans, the fairies are portrayed as lacking either the cognitive abilities or the experience (if not both) to perform tasks like cooking, cleaning, and making clothes. In real life, a person who couldn’t cook or clean for herself wouldn’t be able to live without help, and adults who can’t live without help are often treated rather harshly; but in the case of the fairies, their inability to do these things doesn’t mean they’re seen as defective, but simply that they’re trying to be something they aren’t. Their lapse into using magic again, while it happens at an inconvenient time, is the natural result of putting themselves in an unnatural situation.

Therefore, Sleeping Beauty has a positive portrayal of its “disabled” characters. Their inability to perform normal tasks is humorous, and ultimately not a problem for them, because it is acceptable for them to live differently and rely on other skills to take care of themselves. Humanity is not a goal, but simply something they tried and failed, and then abandoned without seeing their failure as reflecting badly on them.

In The Little Mermaid, however, Ariel’s desire to be a human is a goal that, from the perspective of the movie, she has to achieve at all costs. It wouldn’t really be accurate to say that she desires Eric above all, because she is interested in humans from the beginning and seems to fall in love with him because he’s the first human she sees. While the fairies’ disguise as peasants doesn’t seem like something most viewers could relate to, Ariel’s longing for humanity is more comparable to the way real disabled people are expected to long for normalcy; it’s not just another way of being, it’s an inherently better life.

Objectively, Ariel’s life isn’t bad, but she sees it as inferior: “Flipping your fins you don’t get too far/Legs are required for jumping, dancing,” she sings, ignoring the speed and grace of her own movement. There’s nothing strange about a sheltered teenager being interested in people from another place, but it does become disturbing how Ariel dismisses her own body as nothing but an obstacle to human life, and that this is portrayed as not mere teenage restlessness, but a sensible outlook.

Ariel’s initial life as a human is also comparable to the life of a disabled person trying to be as normal as possible. In real life, a disabled person trying to function as a non-disabled person has to make sacrifices non-disabled people don’t have to make. As a human Ariel can no longer do what she did best as a mermaid (singing), and, most importantly, cannot communicate. (It’s interesting that her inability to communicate keeps Ariel from even being able to tell people that she used to be a mermaid. As is often expected to happen when disabled people are “cured,” she completely drops the identity she had before.)

The Little Mermaid had the potential to be a more unique story about a nonstandard character trying to be normal. In addition to losing her voice, the mermaid in the original story finds it incredibly painful to walk and dance, but does so anyway in order to be attractive to the prince; and she ultimately isn’t able to land the prince, partly because she has given up her ability to communicate so he doesn’t know that she’s the person who saved him. In the fairy tale, the mermaid’s attempt to be human is tragic.

Obviously, the Disney version of the story could not be tragic because that’s not how Disney movies are. But the story could have been given a happy ending in which Ariel went back to being a mermaid without losing her relationship or her zest for life. Instead, the Disney movie glosses over Ariel’s sacrifice, by making her only lose her voice instead of also being in pain; and in the end, she is magically cured of both her lack of humanity and the difficulties that a magical creature trying to be human would have (her voicelessness).

The Little Mermaid has often been identified as a problematic movie in terms of gender, because Ariel changes her body for a man. But it’s also problematic in terms of disability, because Ariel must change herself to a more normal form to realize her dreams. While in Sleeping Beauty, the fairies’ attempt to be human is an impetuous bad idea, it’s presented as the only way Ariel can be happy. Viewers are told not only a)having a normal body is worth the sacrifices, but b)don’t worry about that, because actually, switching from abnormal to normal will become easy and eventually have no drawbacks attached at all.

Labels:

cure,

disney,

metaphor as disability,

movie,

sleeping beauty,

the little mermaid

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)