He was a kid I met this summer at the school where I interned. I have written about him several times, sometimes at length. And although he was my favorite kid at the school, that isn't why Danny is always surfacing in my mind, tiny in his big t-shirts, flinging himself around and reciting things.

It's through Danny that I found out for sure, this stuff is about me.

Because the first thing people use on us is always, "It's not about you." When I was a kid, when I first started reading about autism rights, it was so instinctive: of course it's wrong to say "cure autism now." Of course it's wrong to say autism is a tragedy, a disease, it's wrong to give kids electric shocks, it's wrong to say you thought about killing your kid in a video about eliminating autistic people from the gene pool. Like Sinclair says it's wrong to mourn for a living person. All this stuff was plain and clear and bright, and I was autistic, and I was being attacked.

Right?

Well, not to anyone else.

Because, of course, if I told anyone I was autistic, they said I was lying, or I had a different kind of autism that made me smart and talented, so I wasn't like Those Kids, the kids who needed to be cured. And that I should think about their parents, about the money and time to care for a person like that, about the dreams that are shattered when your kid is really autistic, not smart autistic, the real kind. So in my late teens when I put myself through my paces, when I figured out my deficiencies and set myself to systematically eradicating them, one of the deficiencies I eradicated was my use of the word autistic. Because you shouldn't use words people don't understand. And you shouldn't use words that will make someone feel bad, someone who has a kid who's Really Bad, Really Disabled. Because you're not that.

And I met some autistic kids and they were not much like me, and I didn't know to apply what I knew about myself to them, because I couldn't see what they were feeling inside. But I liked them. Then I met some people with intellectual disabilities and I liked them too; after a brief nervousness because some of them looked so different from me, and made noises I didn't understand, it was easy to like them. They were people who liked things, some of them the same things I liked. I could see that they weren't on the surface very similar to me, but I liked being around them almost more because of that, because it made me feel happy and chastened to misjudge them again and again. To be proven wrong when I thought I could quantify them just because I knew more words.

So by this point, I was pretty much sold, even if I wasn't Really Autistic, on the idea that people with developmental disabilities matter. Because I was around them all the time and it was obvious they mattered. But still, I felt my position was that of an outsider, an ally. I had opinions but I didn't necessarily feel that I had much right to talk about them; I didn't feel I had as much right as the parents or teachers of people with developmental disabilities.

And then I interned at this school.

And I started out thinking: wow, ABA is so cool. I've heard negative things about it from other Not Really Autistic people, but who am I to talk about what these Really Autistic kids need? They can't even talk. They might bite themselves or something. What the hell do I know about that?

And then I met Danny and the other kids in his class. High-functioning kids. Verbal kids.

Tony, who had been nonverbal a few years before, was incredibly hardworking and sweet. When he went into the school director's office and turned out the lights as a joke, I laughed, but she said, "Tony. Look at my face. How do you think that made me feel?" She stood there looking grim until he apologized.

James was stressed out and upset; one of his teachers leaned towards him, staring fiercely into his eyes, talking with cold, strained-sounding words, the kind of voice I called "static" when I was a kid. James looked scaredly back at her, wriggling his hands around in his lap. "James," she said. "I know you're upset. But what you're doing with your hands looks silly." This boy, all the tension in him being channeled into something harmless, something she had to look under the table to see. His tension was silly. His discomfort was an inconvenience. He was eight or nine years old.

And Danny with his words. "Danny's an interesting kid," the school director told me. "He likes to be in charge." Danny and I were walking, holding hands, and when I responded with concern when he told me he was tired, another teacher told me, "He's playing you." It's true that Danny was a bossy little boy; when we played restaurant, he replied, "No, we're out of that" again and again until I ordered the food he wanted to pretend to make. And his love of subway trains spilled out everywhere. He was supposed to write a story about a sad princess, and he did, but half the story was about the princess's friends taking her on the subway to cheer her up. He was supposed to write a crossword puzzle and the clues were things like, "Transfer is available to _____ North." The school was full of subway maps, since many field trips involved subways, and Danny would sometimes just lean over a desk, pressing his face into the shapes and colors, whispering his favorite schedules to himself.

Danny just liked words. When he was using his special words, the weird words he scrounged for or made up himself, he would find himself jerkily hopping across the room, speaking in a squeaky voice, his small face tense with excitement. "Presentation" was a weird word for movie, "document" was a way to talk about the letter he had typed on the computer for his parents. "I went to the barber," he said when I commented on his newly short hair, and then, with a rush of joy, "but I like to call it the hair shop!"

I like words too. It was hard to watch Danny's teachers nudge him, sit down with him, say, "Danny, the word 'presentation' is a little weird; you need to say 'movie.'" It was hard to watch the way they looked at him, pointedly, until he stilled his hopping and lowered his voice to a more standard pitch. When Danny found out my middle name is Wood, he completely tripped out on it, hammering pretend nails into my stomach and giggling, "I'm gonna build something out of you!" "Danny," a teacher said, "don't be weird. You and Amanda were talking about names."

It was the word weird. Nothing foreign my whole life. Tracing words and shapes in the air, crossing myself, my mom asking me a lot of questions, "Have you been feeling the urge to do that lately? Why do you do that?" with so much static it was clear I'd better keep my hands as still as possible when she was around. Running jerkily up the stairs at school, I couldn't help myself until I was fifteen or sixteen, despite the older boys laughing to each other--"is she trying to race you?" Movement just consumed me that way. And being a thirteen-year-old who said "suppose" and "quite" when no other kids did. Just loving words too much, finding it hard to stay away from the strange ones. And getting too excited. Being weird is not that alien for me.

So my divisions broke down a little, because I was watching a kid just like me, and I was learning, in very specific, qualitative terms, what they thought of people like me. I was so nervous about keeping myself still and using the right words because I thought they wouldn't let me intern there if they knew I was actually like Danny, that I didn't think he was weird at all. All of Danny's teachers had been taught to grimace and say how annoying it was when he talked about trains. They watched The Office, but they never ever laughed when Danny told flat, self-referential jokes on purpose, twisting the ones he had been trained to say. I thought Danny was funny. Every time I talked to him I felt nervous about doing something that his teachers would think was wrong, and I also felt bad about perpetuating the attitude he was being taught, that none of the things he loved mattered.

So from specific to general, from Danny to James and Tony, to Max and John. John's teacher made him walk, in stiff, clean steps, and if he started doing anything that looked like skipping or jumping, she grabbed his arm, said "No," forced him again and again. Max liked to move his arm in circles while he was watching TV, so he was hauled off into an office, pushed down into a chair, had mouthwash forced into his mouth while he cried. They told me they were narrowing it down, he was moving less and less. Max and John didn't talk. James and Tony didn't talk as well as I do. But I move too much, and I move wrong, especially when I was a kid, and in that school I saw what they do to kids who move wrong.

I realized that, actually, a lot of it was about moving wrong. Or talking wrong, if you could talk. Or just taking too much initiative--wanting to make up songs, like Danny did, or playing a practical joke, like Tony did. That these kids looked and acted different and the school wanted to control them and make them as still and docile as they could possibly be. Watching them treat hopping, rocking, and neologisms like you'd treat a bomb on an airplane--it was like being at summer camp with a kid from the south, sitting in a car uncomfortably while he said he'd kill a gay person if they ever came near him. Wanting to say, no, it's not anything important; I'm like that, see? But I didn't talk in the car and I didn't talk in the school.

This is too long. It's hard to even explain it. I just have to say, for the millionth time, that this whole functioning level thing--yes, it matters in certain ways. I can buy and cook food for myself, while a severely autistic person probably can't. I can hide the way I move and talk better than other people can. But this doesn't really have much to do with politics, because when people claim that "cure autism now" and the disease and the Judge Rotenberg Center are not about me, well I beg to differ. The only reason they're not about me is that I'm old and verbal enough to not be vulnerable to that kind of abuse. They would be all too happy to practice it on me if they could. Autistic people do not get abused because they are low-functioning, they get abused because they do weird things.

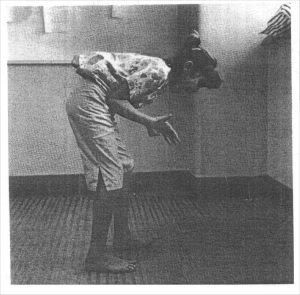

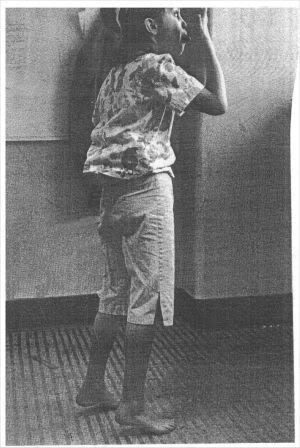

So, the old-school ABA trials? With Lovaas?

This is a kid getting an electric shock:

This is why:

If you were in the wrong place at the wrong time, the wrong age, the wrong functioning level, this could be your life. This what people like them think about people like us.